BORDER ELASTICITY

#Urban Connectivity

#Heritage Revitalization

#Inclusive Campus

#Transit Oriented Development

#Public Space

Exhitbitor

Patrick Cheng-Chun HWANG,

Justin Wat Tat CHENG,

Po-Min KUNG

Team Member

Ke-Jung CHEN,

Yi-Hsien TSENG,

Yen-Shan LEE,

Yi-Fang LAI,

Wei-Tzu HUANG,

Wei-Cheng FANG,

Ting-Wei HSIEH,

Yu-Wen HUANG,

Tzu-Yun TSENG

View the Printed Edition (PDF)

Border Elasticity: Thick & Thin

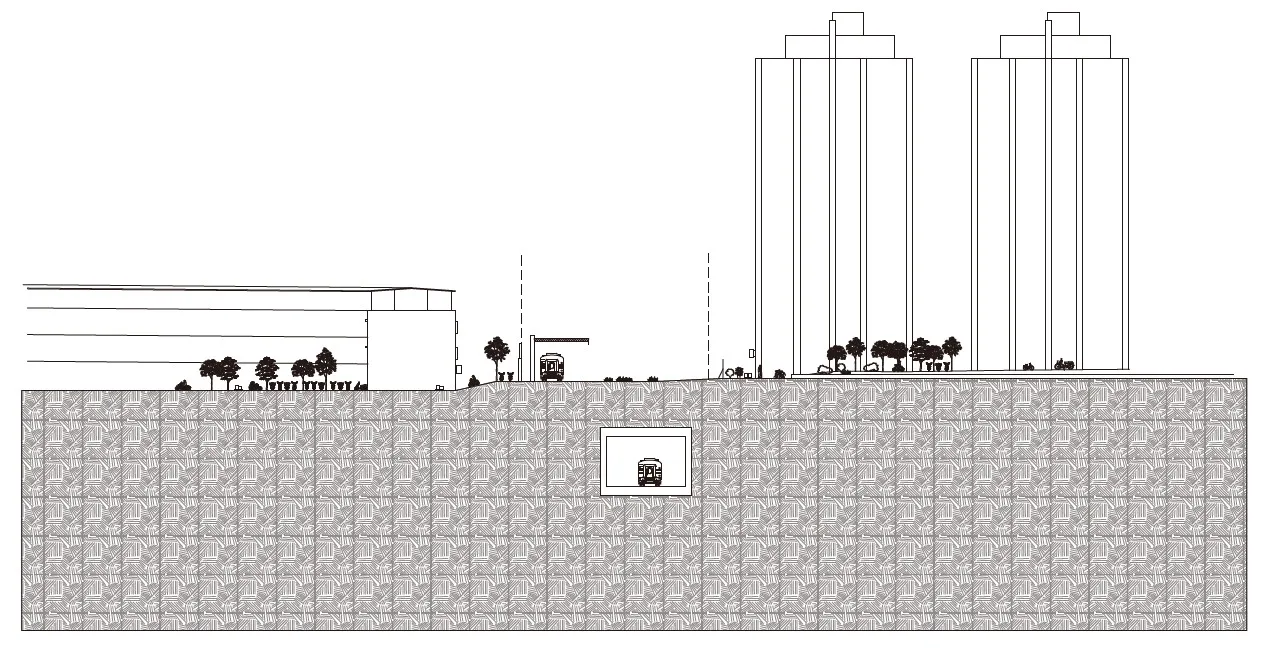

The Tainan Railway Underground Project is not merely a technical achievement in infrastructure but also a significant turning point in urban development. As the railway disappears from the ground level, the previously dividing space is liberated, offering an opportunity to reconnect the east and west urban blocks and revitalize community life. This transformation reshapes the city’s structure and opens up new possibilities for public spaces.

This exhibition explores the concept of “Border Elasticity,” examining how a functional divide transforms into a fluid public connection. We aim to showcase the dynamic balance between environmental sustainability, community engagement, and historical preservation in urban spaces. Reflecting the theme of the 19th Venice Architecture Biennale, Intelligens: Natural, Artificial, Collective, the exhibition uses Tainan as a case study to consider how architecture and public spaces can embody collective intelligence in an uncertain global era.

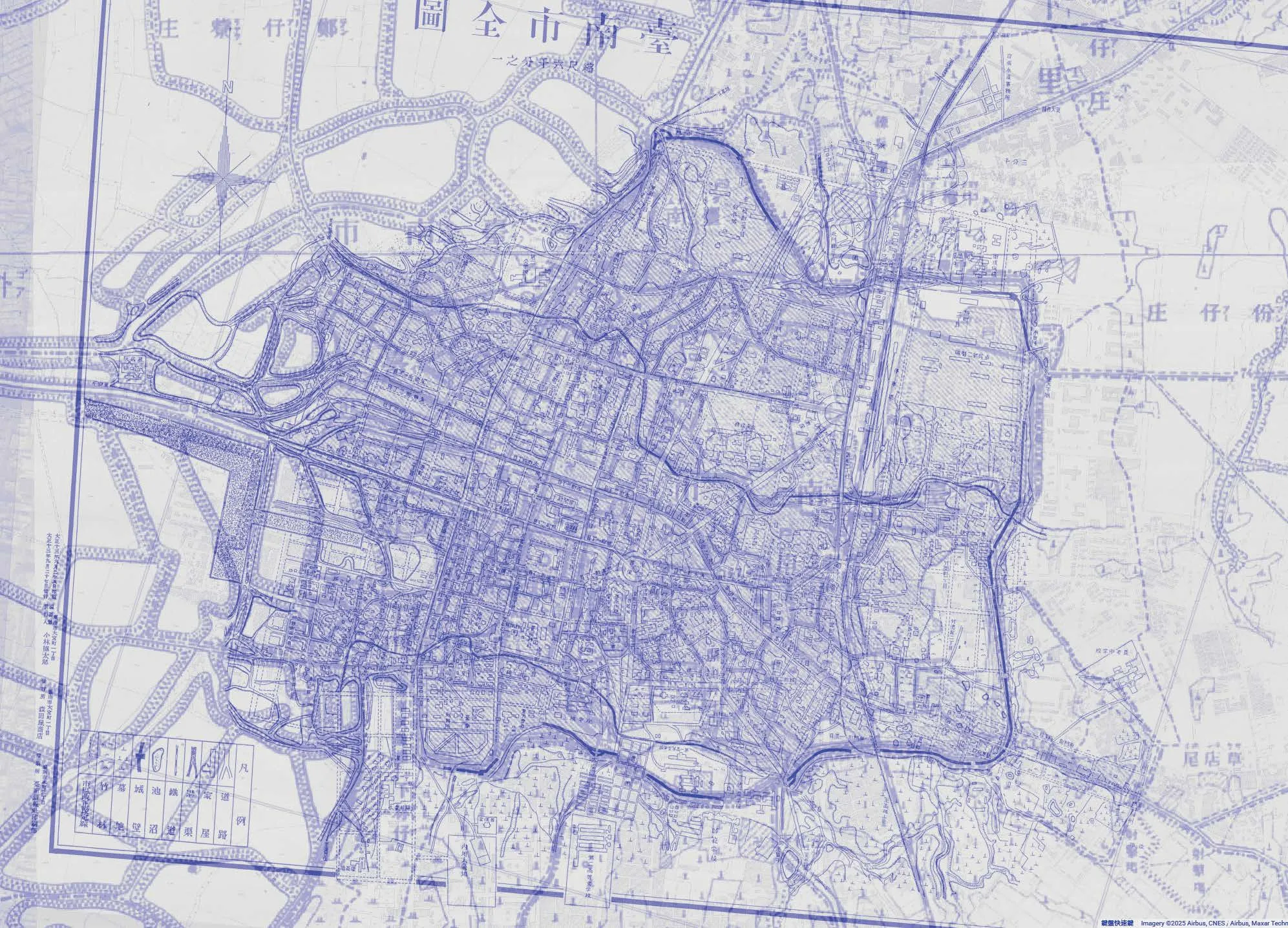

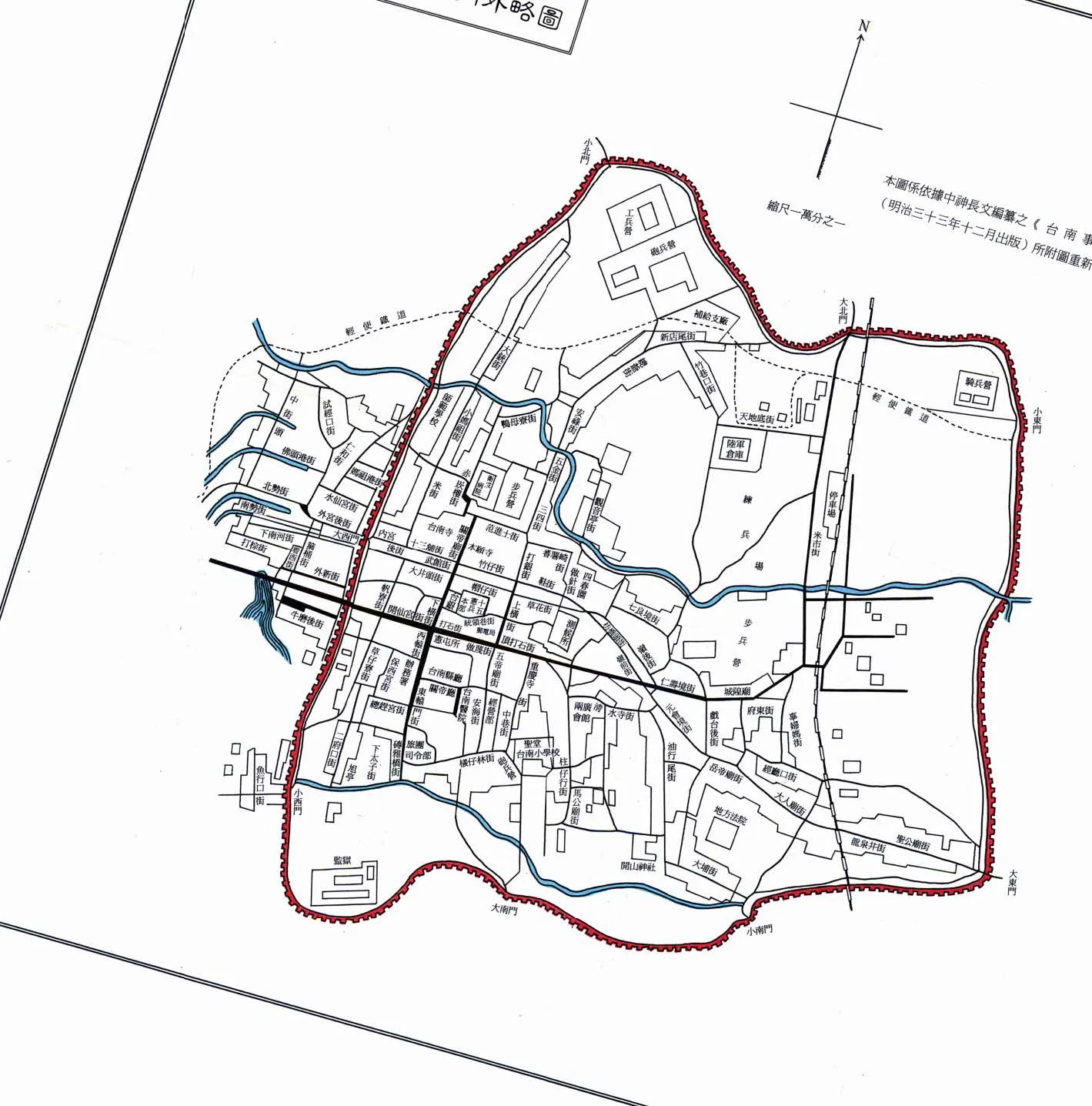

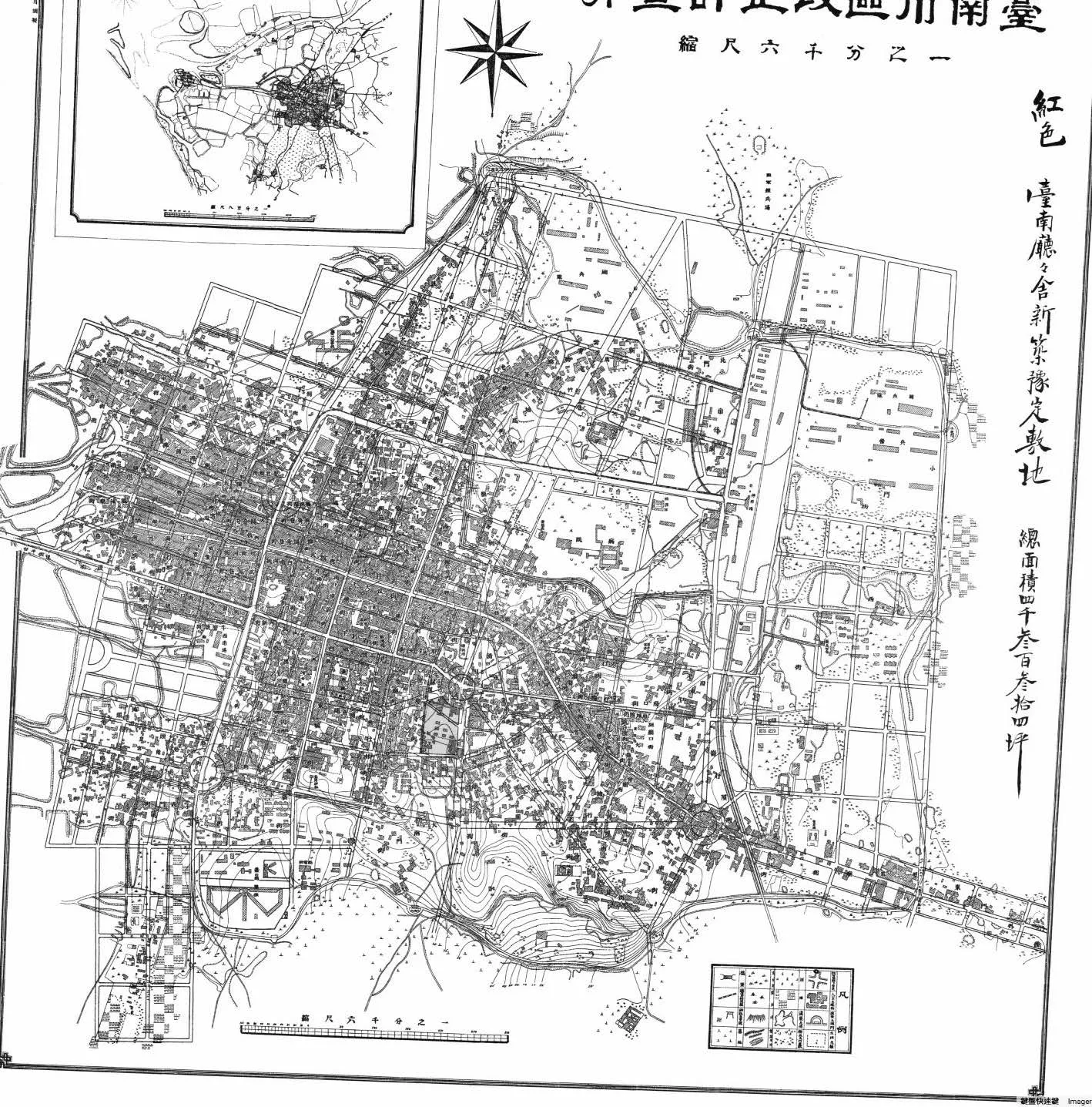

Layered Time

Tainan’s political and colonial history parallels and mirrors the arc of its urban form—a narrative of presence and erasure. Border Elasticity¹ seeks to illuminate the echoes between Tainan’s past and future, tracing and projecting its developmental journey.

The city’s fortified origins date back to 1624, when the Dutch built “Fort Zeelandia” near the presentday Anping harbor. In 1725, under the Qing dynasty, an expansive city wall was constructed, defining the urban core that persists today. These fortress walls were later deemed regressive by Japanese colonizers, who “de-fortified” them. Rather than constructing city walls, they introduced an island wide rail system instead. This rail network symbolized modernity, but created new boundaries that divided the city into Eastern and Western parts. After the Second World War, Tainan’s urban fabric continued to evolve, shaped by the Nationalist government, which assumed control of Taiwan in 1949.

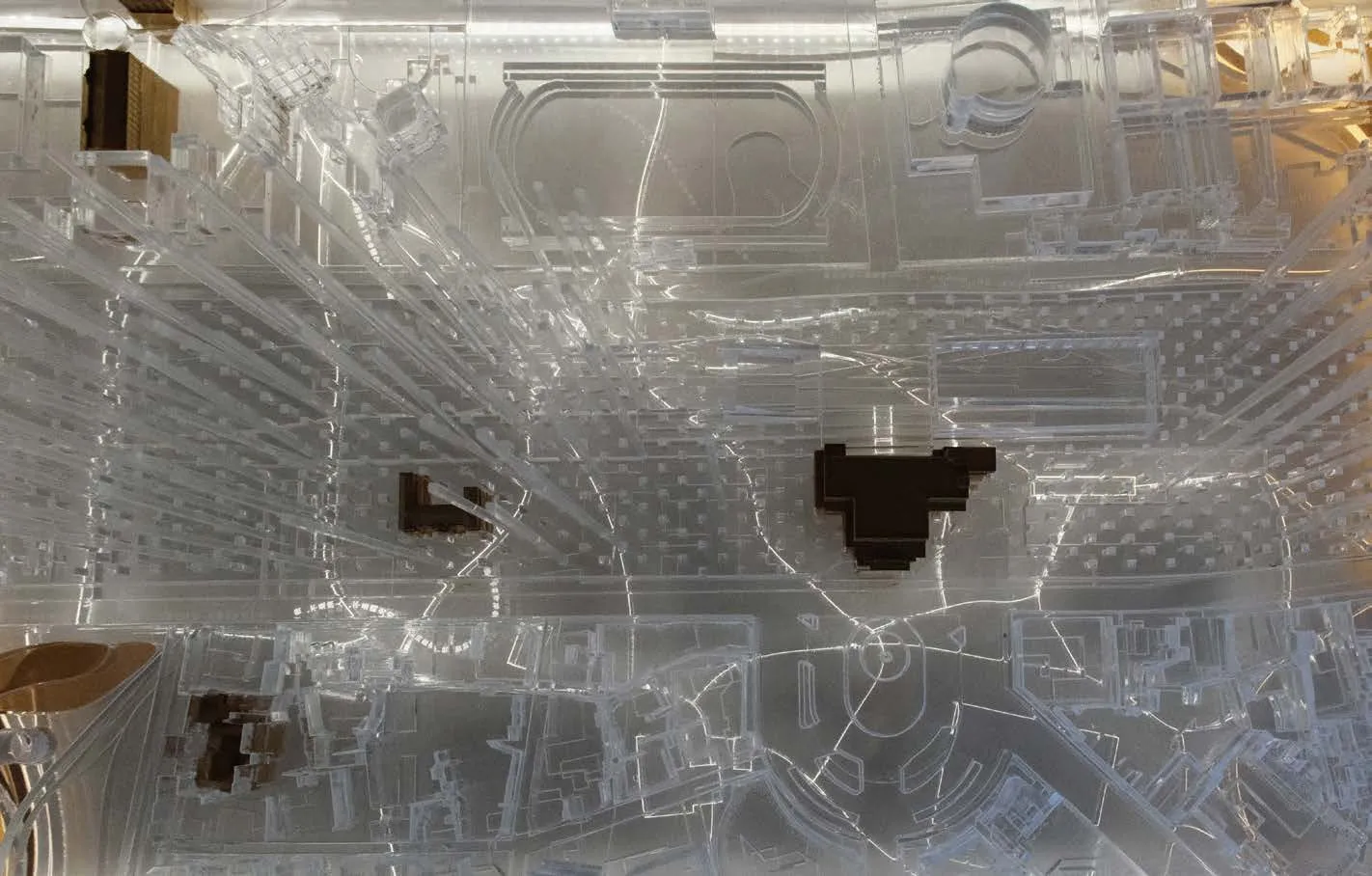

History is precise and specific, yet impossible to represent. To reflect Tainan’s key historical moments, Border Elasticity abstractly mapped the city’s history and reimagined it through four crystal archeological strata². These layers form the foundation of a city that remains in flux, resilient and adaptable. Over the next decade, Tainan will undergo significant metamorphosis. The groundlevel train system, once modern, is now seen as a relic of the 19th century. Its proposed underground relocation offers a unique opportunity for National Cheng Kung University (NCKU), which has bordered this historic divide for 60 years. As the largest institution near this site, NCKU is seizing this pivotal moment to reconnect the city’s districts, fostering inclusive, educational, cultural, economic, and environmental integration.

875 Tainan Street Map

875 Tainan Street Map

1900 Tainan Street Map

1900 Tainan Street Map

1911 Tainan Street Planning Map

1911 Tainan Street Planning Map

1970 Tainan City

1970 Tainan City

1975 Aerial photographs taken by the U.S. military

1975 Aerial photographs taken by the U.S. military

1986 Tainan City Urban Planning Blueprint (Blueprint Copy)

1986 Tainan City Urban Planning Blueprint (Blueprint Copy)

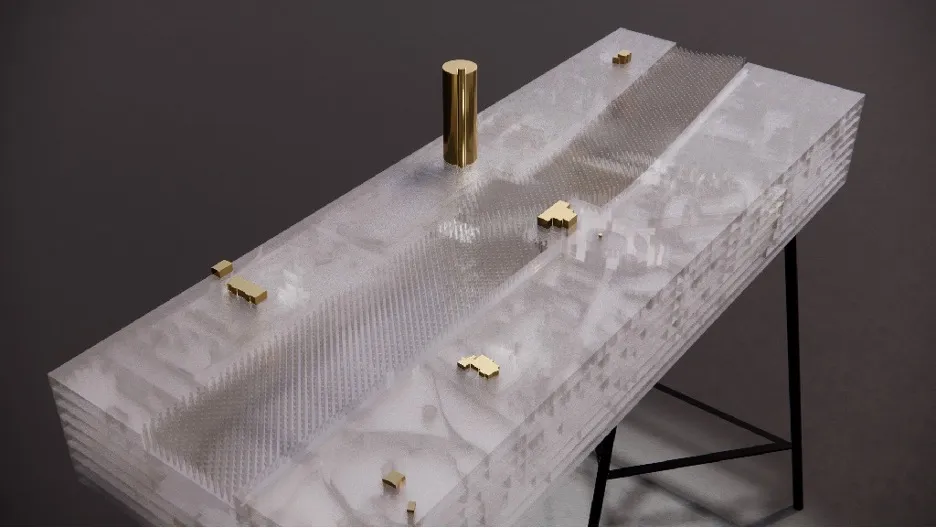

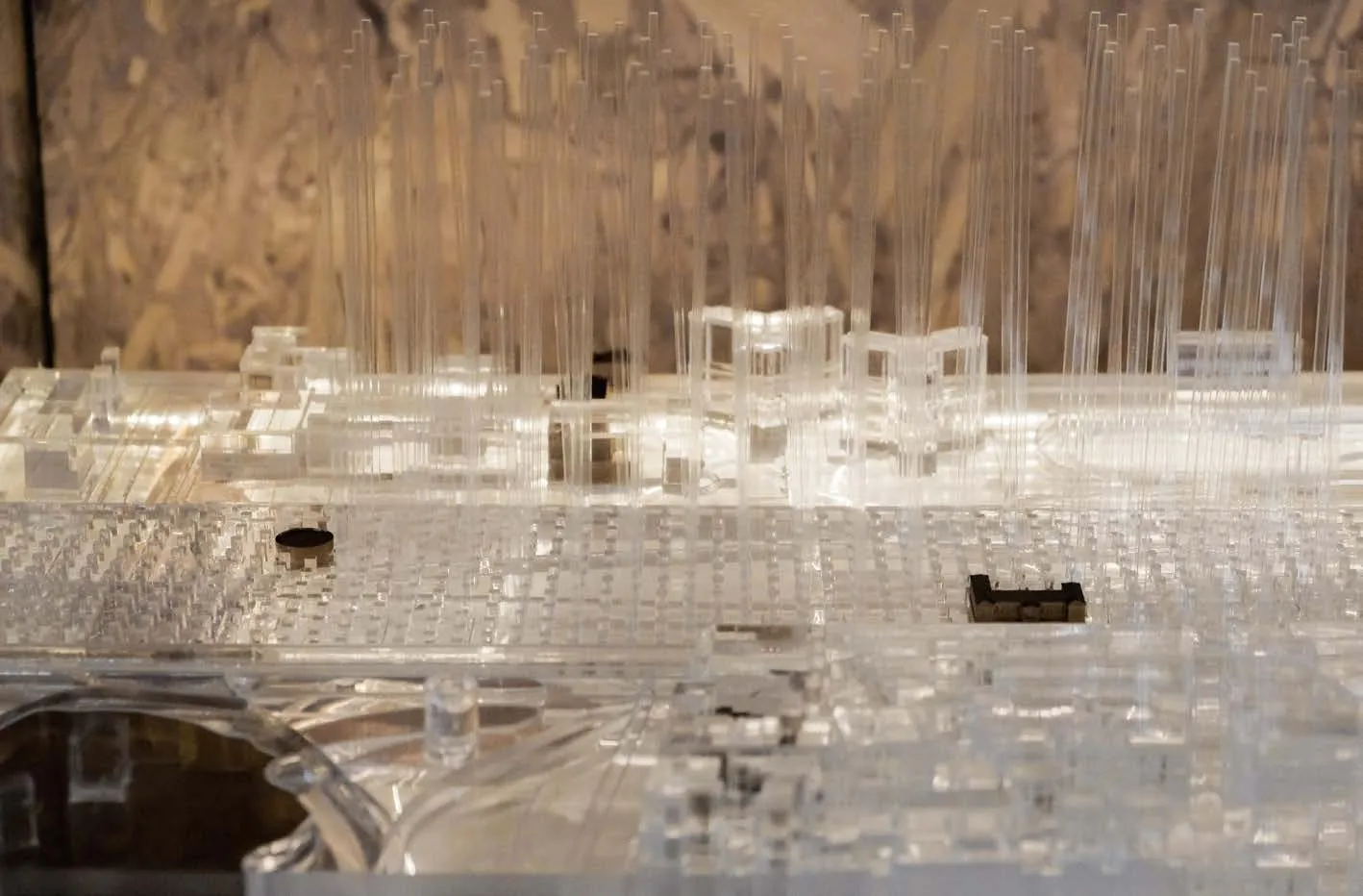

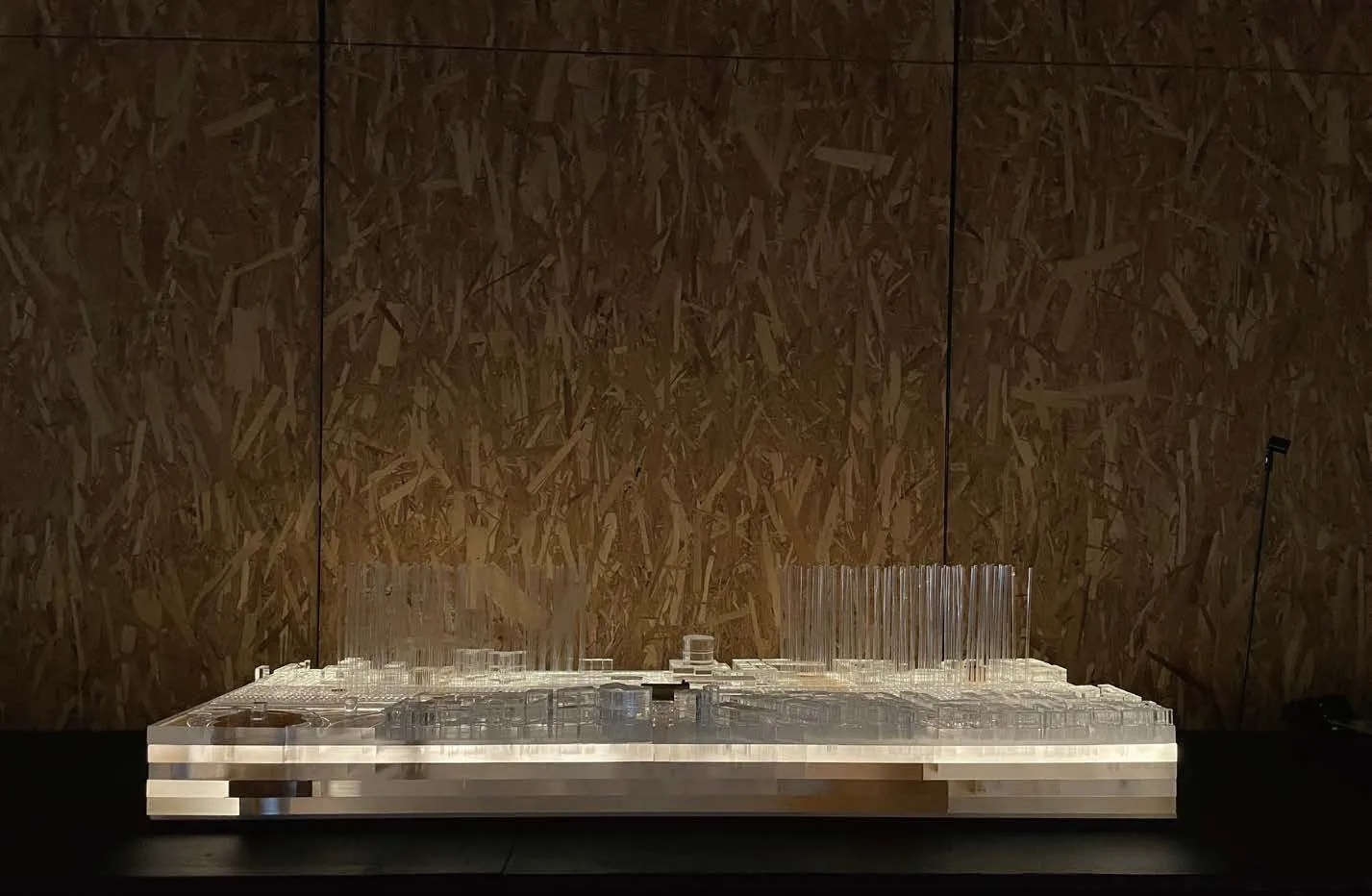

Crystal Strata

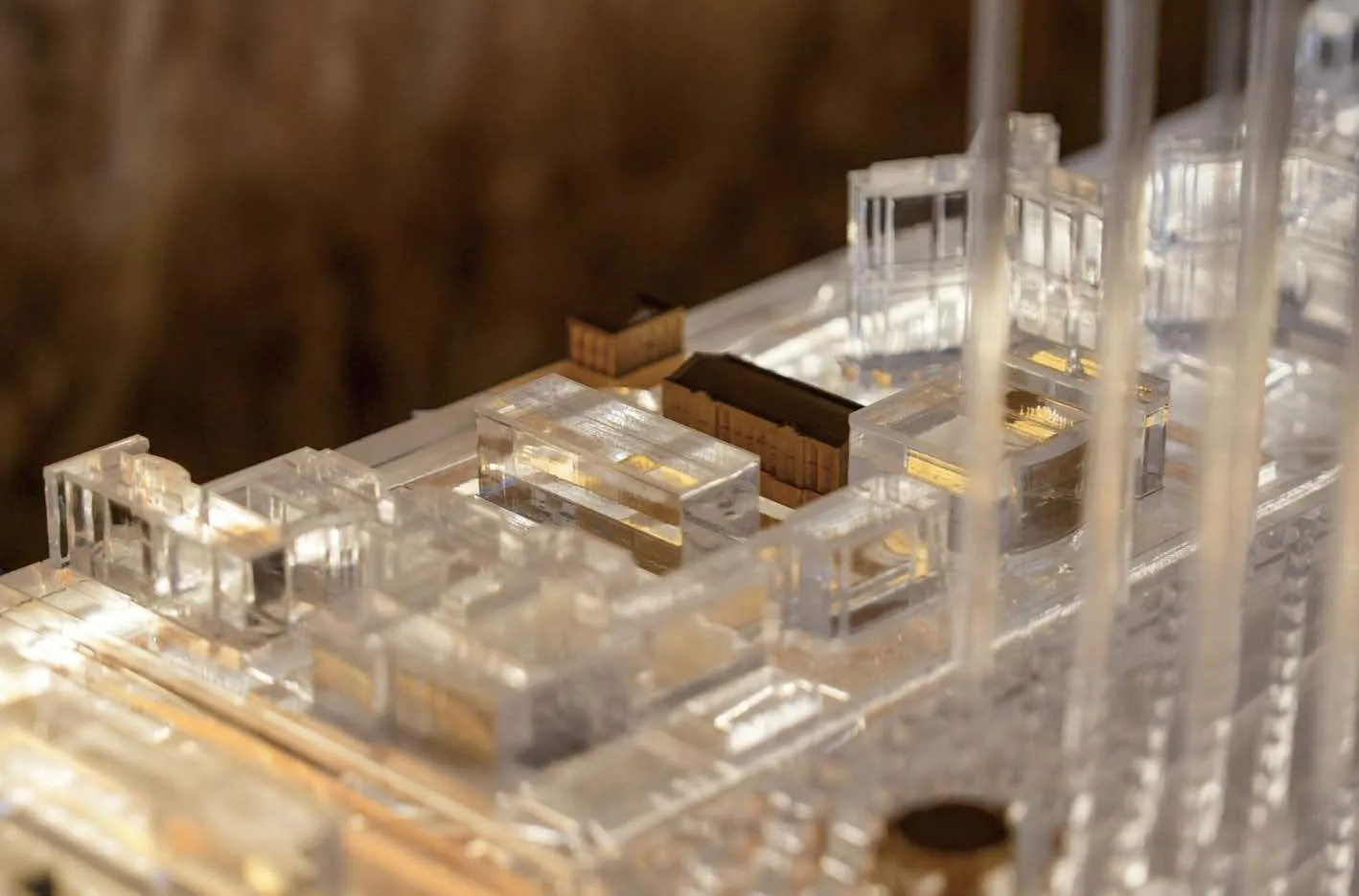

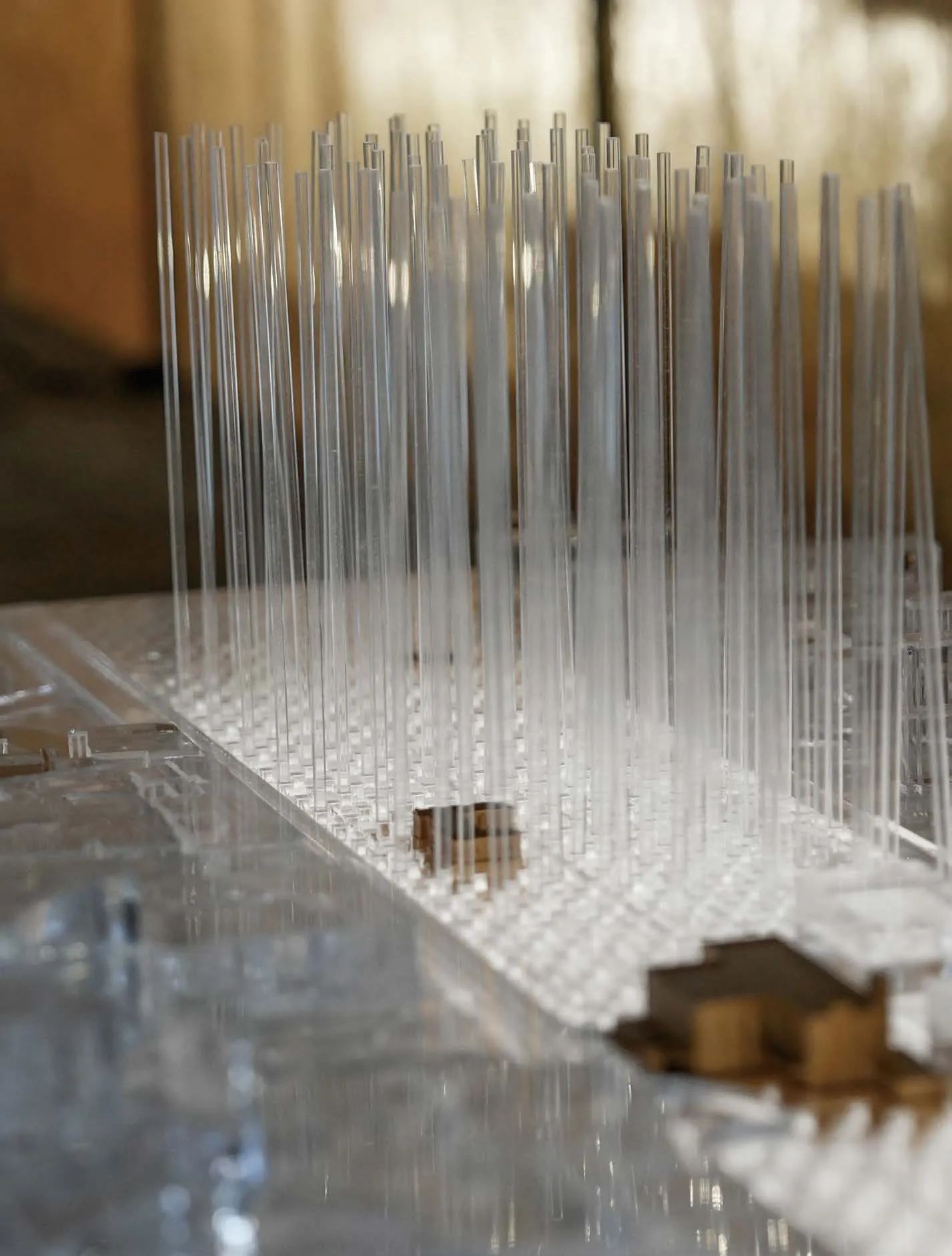

The four lower crystal archeological strata represent distinct epochs in Tainan’s history, while heritage buildings are transcendental artifacts stretched across the epoch strata, connecting the past and present. At the uppermost layer, 1,240 sunken squares are carved across the terrain of Border Elasticity. From these squares rise crystal columns, each a beacon of the future.

Designed with conceptual elasticity in mind, these columns invite different interpretations—literal and metaphorical. Initially conceived to represent the economic potential of the zone’s floor area ratio, the crystal columns can also be seen as urban sculptures; resembling blades of grass; or pencil towers. Metaphorically, their arrangement evokes the ritual act of placing Daoist incense or cathedral candles, resonating with Tainan’s cultural and spiritual identity. Each sunken square might even symbolize 1,000 of Tainan’s current residents, grounding the city’s vision for the future people.

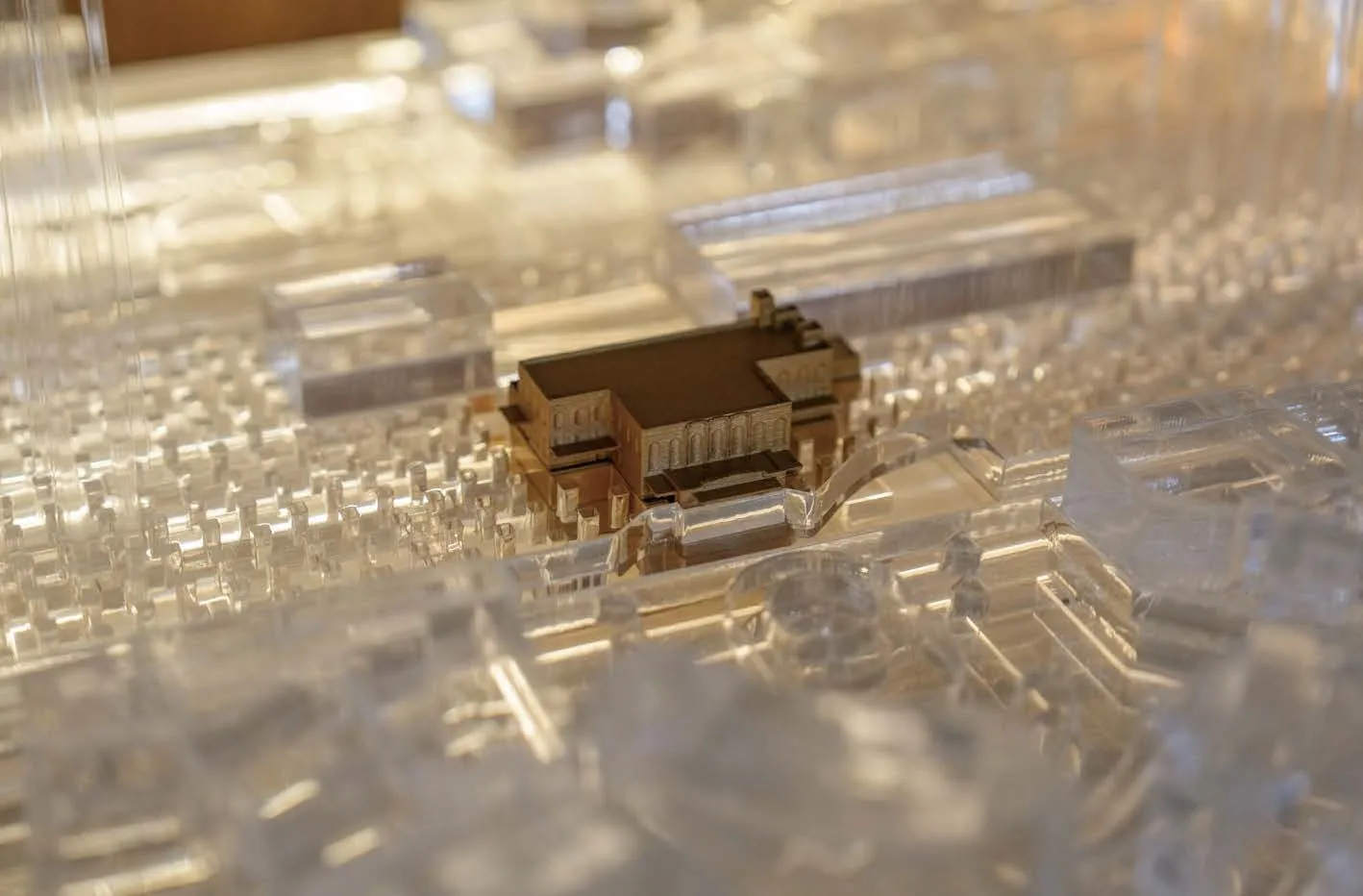

As Taiwan’s oldest city, Tainan also holds unparalleled archaeological potential. Excavations for the underground train tracks, which began five years ago, have unearthed colonial-era edifices, ruins, and relics. To celebrate these discoveries, including the covered creeks and waterways, the project preserves and highlights these historical treasures as golden artifacts, displayed at their original sites, celebrating the city’s heritage.

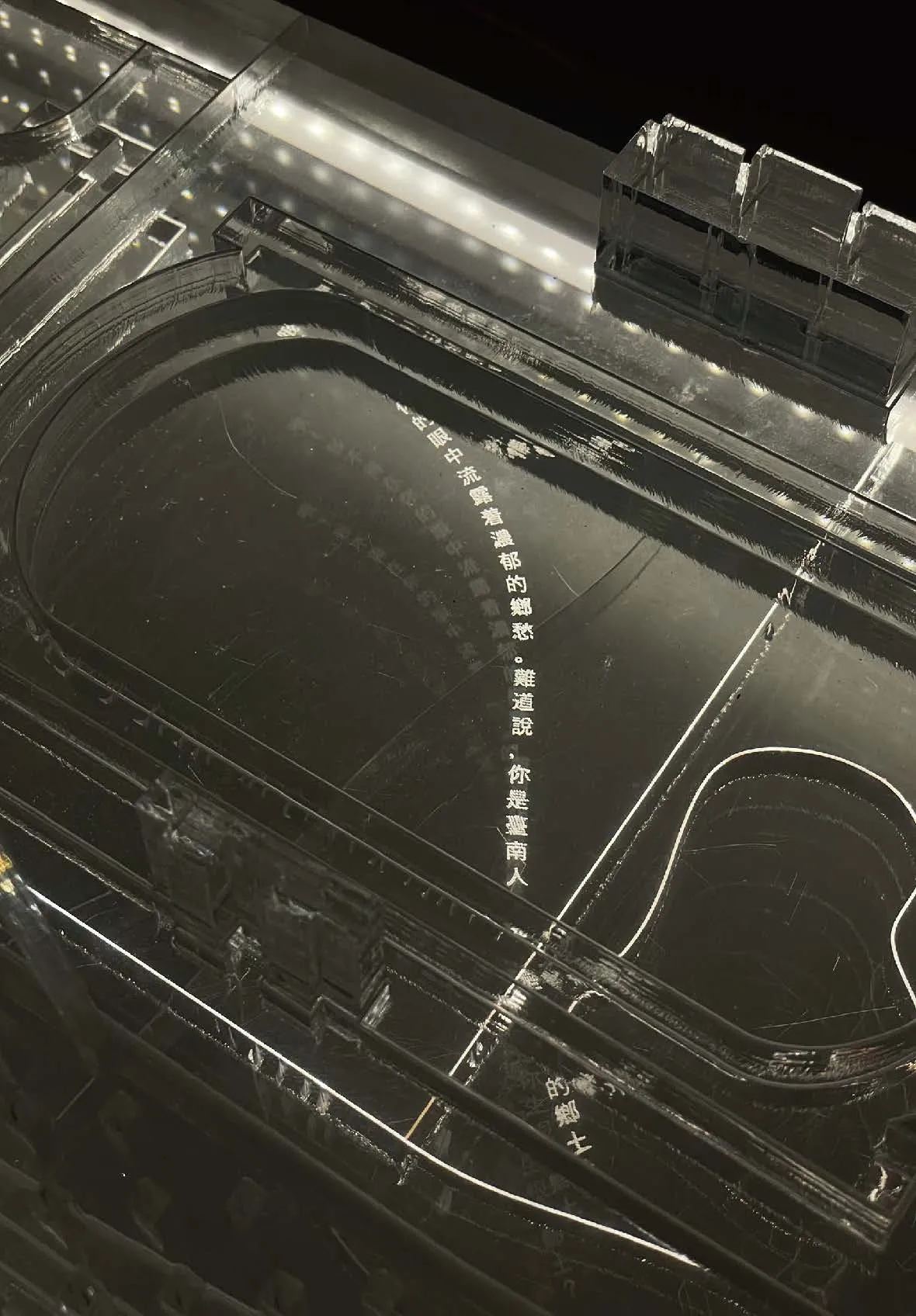

Poetry in the City

Laced within the crystal layers of Border Elasticity is a poem by native Tainanese poet Quo Fung³. The poem alludes to the history of Tainan through the story of a nomad returning home, seeking clues to his identity. The poem is gently engraved into the crystal strata, only visible through refractions, echoing the hidden cultures and phenomenological urban life of Tainan inside its winding alleyways and urban corners.

Border Elasticity Physical Model

Border Elasticity Physical Model

Crystal symbolize the historical treasures hidden in Tainan city.

Crystal symbolize the historical treasures hidden in Tainan city.

Crystal archaeological layers represent four distinct eras in Tainan.

Crystal archaeological layers represent four distinct eras in Tainan.

The old train station is rendered in gold

The old train station is rendered in gold

The Japanese colonial building located within NCKU.

The Japanese colonial building located within NCKU.

An interactive crystal column invites diverse interpretations.

An interactive crystal column invites diverse interpretations.

“Tainan Reflection”

Who are you? You, the lonely traveler, why do you always linger over these ancient scrolls? It is a summer evening, the radiant red sunset Hangs above the seas beyond Anping Harbor. Shouldn’t you embrace these beautiful feelings, Go to the beach and listen to the distant sound of the waves? Or perhaps, visit the Shrine of Koxinga, Sit beneath the withered old plum tree in the backyard, And savor the solitude of the centuries. In Tainan, if you don’t seek out these places, What else could you be searching for?

I? I am neither a traveler nor a passing tourist. Returning to Tainan, I seek my old home, The footprints of my youth. Tainan, in my heart, is an eternal city. No matter where I go, It always appears in my dreams.

Oh! No wonder your eyes reveal such a deep longing for home. Could it be that you are Tainanese, And this is the land where your roots are planted?

If you ask me whether I am from Tainan, I would say: Yes, and no. Truly, I don’t know where I truly belong. I was born in northern China, But I lived there so briefly That I left before I could form memories. Since then, I’ve drifted east and west, Through countless cities, countless villages, And so many unfamiliar places passed before my eyes.

What can I say? Perhaps I should admit I have no fixed hometown. My origin is written in my skin, etched in my face. I am a person of east, west, south, and north. Don’t ask me where I come from—it doesn’t matter. What matters is to love this land, As a child loves their mother. Yes, how could I suppress my deep love? For the place that nurtured me, That helped me grow— It is Tainan.”

Dynamic boundaries from infrastructure, history, and urban.

Dynamic boundaries from infrastructure, history, and urban.

Urban forms are sculpted by the layering of distinct historical epochs.

Urban forms are sculpted by the layering of distinct historical epochs.

Golden historical architecture is paired with dynamic crystal columns.

Golden historical architecture is paired with dynamic crystal columns.

The dynamic interplay of urban strata and boundaries.

The dynamic interplay of urban strata and boundaries.

Border and Boundary

Submerging Tainan’s old train tracks underground offers a transformative opportunity for urban development, recalling Richard Sennett’s distinction between borders and boundaries⁴. In natural ecosystems, he argues, borders are vibrant zones of interaction and exchange, while boundaries are rigid, isolating barriers that hinder growth. Above-ground train tracks often act as boundaries, splitting neighborhoods, disrupting pedestrian movement, and creating underutilized or deteriorated spaces. Moving these tracks underground can turn them into border-like spaces, fostering connectivity and collaboration.

Sennett’s exploration of porosity and resistance in human systems highlights the benefits of underground infrastructure. Removing the physical and visual barriers of surface-level tracks creates open space for public use—parks, playgrounds, and shared environments—transforming these areas into active zones of interaction, much like ecological borders. Submerging Tainan’s tracks aligns with sustainable urban design principles, enhancing wind flow, accessibility, and integration while revitalizing public life. The proximity of NCKU further amplifies this transformation, enriching daily urban experiences for residents & students.

City as University, University as City

As Tainan celebrates its 400th anniversary, Border Elasticity envisions a future that reconnects NCKU with the historic Central West District through the strategic subterraneanization of train tracks and the transformation of Tainan Central Station. This vision reimagines the rigid barriers of the centuryold railway as an “elastic border” that adapts to urban needs, bridging NCKU’s campus with the cultural vitality of the Central West District.

Pathways for open and spontaneous encounters between students, residents, and visitors connect academic plazas, heritage markets, and communal green spaces, erasing the divide between “university campus” and “city.” By fostering integration and interaction, Tainan moves toward a cohesive and adaptable urban future that honors its rich, living history.

Border Elasticity_Research Diagram

Border Elasticity_Research Diagram

Tainan’s urban life by the railway

Tainan’s railway has long connected the city to the outside world, yet it has never fully integrated into its living zones. This separation has turned the railway into Tainan’s “backside” — a vital transportation artery and a boundary beyond urban life and commercial activity. Over time, residential areas expanded along both sides, transforming the railway’s surroundings into evolving spaces that reflect the city’s growth while becoming part of daily life.

Today, living spaces closely border the railway, with residents accustomed to its presence crossing it via pedestrian bridges. While the railway may divide the city, it has also created semi-private spaces where communities gather and life quietly thrives, offering a slower rhythm in contrast to urban development.

Beyond infrastructure, the railway is part of Tainan’s everyday pulse. Amid the city’s rapid changes, it holds more than just distance and speed—it preserves the unhurried moments that define urban life.

The train passing behind the command platform.

The train passing behind the command platform.

The communities once connected by a pedestrian bridge.

The communities once connected by a pedestrian bridge.

The 130 km/h EMU3000 train and the school playground.

The 130 km/h EMU3000 train and the school playground.

The Land God temple beside the railway.

The Land God temple beside the railway.

Between the platform of Daqiao Train Station and the residential area.

Between the platform of Daqiao Train Station and the residential area.

The community activity center beneath the overpass.

The community activity center beneath the overpass.

The Hidden Side of Tainan City

The Hidden Side of Tainan City

The gap between urban planning and daily life

The Tainan railway relocation has reshaped the city’s transportation network and redefined the spaces along its corridor. Previously the city’s “backside,” the railway’s removal has created large open spaces, turning them into urban “fronts.” However, these areas feel disconnected from daily life. Once intimate, community-focused spaces are now forced to open up, facing the challenge of becoming public domains.

Schools near the railway have also been impacted, with their boundaries now exposed to wider visibility. The relationship between campuses and neighborhoods requires redefinition, balancing openness & privacy while adapting to dynamics.

The vast spaces left by the relocation highlight a tension between human-scale activity and large-scale infrastructure. These areas often feel impersonal and disconnected, as everyday routines struggle to adapt to their scale. To succeed, urban planning must ensure these spaces integrate meaningfully into residents’ daily lives.

The large vacant space between the school and the residential complexes.

The large vacant space between the school and the residential complexes.

The park between the residential complexes faces a railway wall.

The park between the residential complexes faces a railway wall.

The previously impassable railway seems like the backside of the city.

The previously impassable railway seems like the backside of the city.

The undefined emptiness between cities.

The undefined emptiness between cities.

The fragmented plots of land in the city under railway planning.

The fragmented plots of land in the city under railway planning.

The Scale Differences Within Tainan City

The Scale Differences Within Tainan City

The autonomy in the extension of living space.

The Tainan Railway Eastward Relocation Plan has created a temporary boundary within the city, where residents tend to park vehicles or store items on both sides, treating it as a temporary storage space. Due to a lack of clarity about the future development of this area, residents have not actively planned or engaged in its use.

This situation highlights a disconnect between urban planning and the daily lives of residents. Without clear plans or communication, residents use these spaces pragmatically, leading to their underutilization. Additionally, these temporary uses can impact the city’s landscape and environment.

To bridge this gap, it is crucial to enhance communication with the community, understand their needs, and collaboratively develop plans for the future of these spaces. Encouraging residents’ active participation in community planning will foster a sense of responsibility and identity toward public spaces. These temporary boundaries can be transformed through collaboration into vibrant public spaces that meet community needs and enhance the city’s overall quality.

People gather under the tree by the railway, having lunch.

People gather under the tree by the railway, having lunch.

The void left behind after the demolition of the overpass.

The void left behind after the demolition of the overpass.

The demolished overpass became a parking space for residents.

The demolished overpass became a parking space for residents.

The Border Between Railway Construction and Everyday Life

The Border Between Railway Construction and Everyday Life

Flexibility and Diversity of Spaces: Redefining Urban Spaces and Revitalizing Communities in Tainan

The railway undergrounding project has provided Tainan with a major opportunity to redefine urban spaces and revitalize community life. This initiative aligns closely with Tainan’s broader urban development strategy, aiming to alleviate traffic pressures, enhance land use efficiency, and strengthen connections between east-west neighborhoods. Historically, the railway acted as a barrier dividing the city’s north and south, hindering traffic flow and leading to inefficient land use. With the advancement of the undergrounding project, the space previously occupied by the railway has been reclaimed, unlocking immense potential for public space regeneration community integration.

These newly planned spaces demonstrate flexibility and diversity, facilitating east-west connectivity and providing residents with places for leisure and relaxation. They can host a variety of activities, including temporary public events, enhancing urban vitality and meeting the needs of diverse groups. These multifunctional public spaces have become focal points of urban life.

The redevelopment of the railway corridor balances historical preservation and modern needs. For instance, the second-generation Tainan Station building, constructed in 1936, has been preserved and restored, serving as a vital link between the city’s past and future. This cultural landmark retains its historical value while being transformed into a shared public space for residents and visitors. The post-undergrounding spaces are not just physical transformations but also reflections of cultural and social values.

Additionally, the reclaimed land has revitalized community life and stimulated economic development. The reconnection of east-west street grids has mitigated the isolation caused by the railway. New public facilities and open spaces serve as venues for interaction, improving residents’ quality of life and strengthening community cohesion. The inclusivity of these spaces provides opportunities for people of all ages and backgrounds to participate equally in public life, fostering a more inclusive society. These spaces also create opportunities for local economic growth, attracting creative industries, small businesses, and cultural tourism projects that invigorate surrounding areas. The preservation and presentation of historical and cultural assets enhance the city’s appeal to tourists, creating shared memories for residents and visitors. Postundergrounding, these public spaces have become platforms for emotional connection and cultural experiences, beyond their functional roles.

This project exemplifies the flexibility and diversity required in urban design, enabling the reorganization of the city’s structure and the reshaping of public life. It effectively addresses transportation and land use issues while creating opportunities for cultural, economic, and social interactions. The railway undergrounding project harmoniously balances historical preservation and modern needs, highlighting public participation’s value in urban planning. It serves as an inspiration and model for Tainan’s future development.

Border Elasticity

“Border Elasticity” is a vision for an adaptable and inclusive urban future that celebrates Tainan’s living history through the opportune subterraneanization of the train tracks. It aims to bridge the NCKU’s campus life with the cultural pulses of the historic Central West District.

References

- See Soja, E. W. (1989) in Postmodern Geographies: The Reassertion of Space in Critical Social Theory. Verso, where he discusses spatial theory and the elasticity of urban and social boundaries as dynamic constructs shaped by historical and political forces.

- See Lucas, G. (2001) in Critical Approaches to Fieldwork: Contemporary and Historical Archaeological Practice. Routledge, where the interpretation of historical strata and their significance are discussed in shaping urban narratives.

- Guo F. (1985) Eternal Island. New Land Publishing House.

- See Sennett, R. (2018) in Building and Dwelling: Ethics for the City. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, where Sennett explores the distinction between built environments (boundaries) and lived experience (borders), offering insights into how cities can foster openness and interaction rather than division.