Mazu Techple

#Kuroshio Current #Monsoons #Mazu #Windfarm #Constructing belief

Exhibitor

Wan-Jen LIN,

Ching-Mou HOU,

Yu-Hsiang YEH,

Po-Wei LAI

Exhibition Team

studio HOU x LIN + Yu-Hsiang Yeh + Po-Wei Lai

Team Member

Yu-Hua TSAI,

Bing-Syun LI,

Yu-Ya WANG,

Jing-En CHOI

View the Printed Edition (PDF)

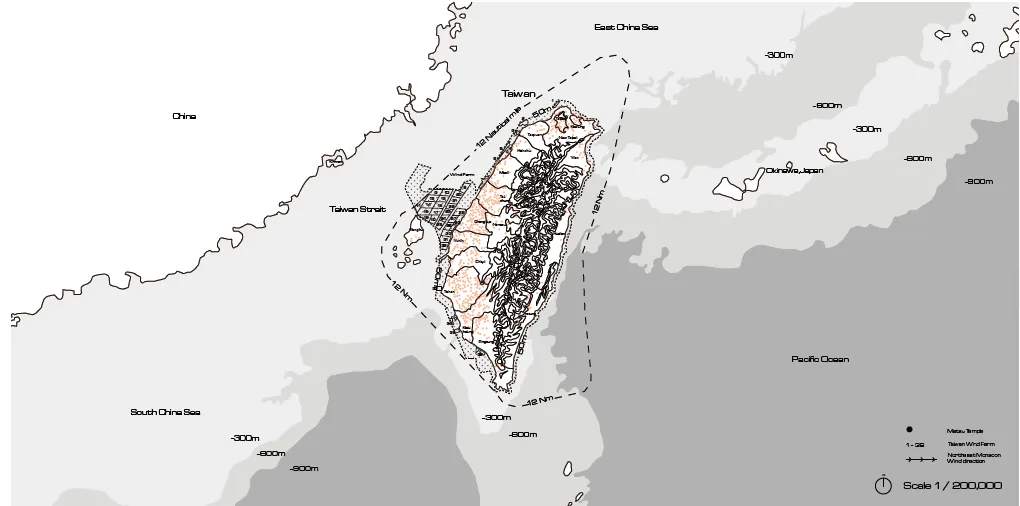

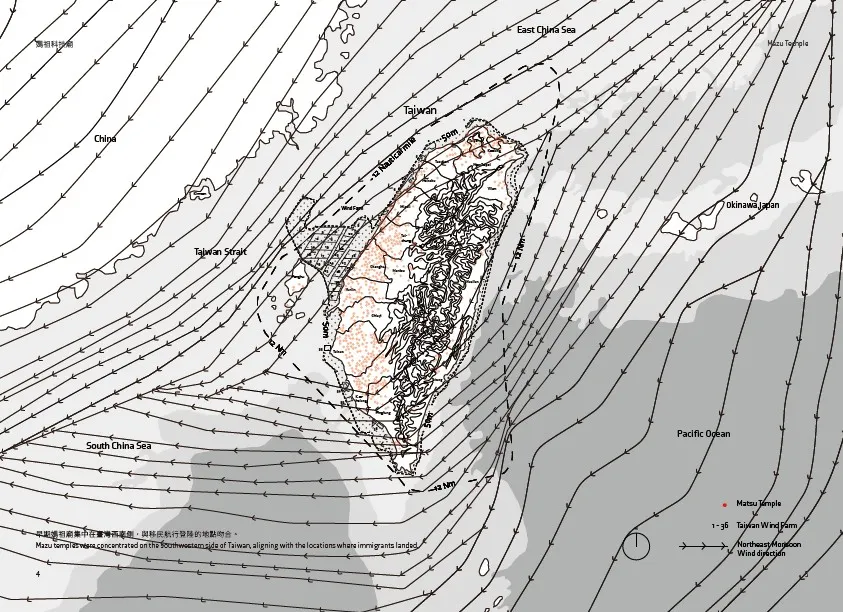

The Taiwan Strait has often been referred to as one of the most dangerous places in the world:wedged between the world’s largest landmass and ocean, the monsoons and ocean currents crossing the strait not only shaped Taiwan’s natural landscape but also deeply influenced the lives of its people, molding both its belief and non-belief. For centuries, the risks and challenges of this sea have nurtured Taiwan’s unique religgious culture, which today has transformed into the spiritual backbone of Taiwan’s national protector mountain. The Matsu belief, which took root in Taiwan, has evolved over centuries, and today it is a vibrant expression of diverse forms.

Belief is the deepest form of spiritual solace, and people always respond to their belief with the best they have. Today, people’s expectations of belief remain the same. The core issue we face is how to build a space of belief that resonates with both elderly and young worshippers, using available construction methods that address current issues.

Beigang Chaotian Temple, the most renoened Mazu Temple in Taiwan

Photo by Yu-Hua Tsai

Beigang Chaotian Temple, the most renoened Mazu Temple in Taiwan

Photo by Yu-Hua Tsai

Protector of Sea Voyagers

Mazu Statue in Beigang Chaotian Temple

Photo by Yu-Hua Tsai

Mazu Statue in Beigang Chaotian Temple

Photo by Yu-Hua Tsai

Mazu Statue in Beigang Chaotian Temple

Mazu, originally named Lin Mo, is the sea goddess of the Minnan region, protecting fishermen and sailors. Crossing the Taiwan Strait was extremely dangerous due to the intense turbulence caused by the north-south monsoon currents and the narrowing of the strait’s cross-sectional area.The rough waves and strong winds made every journey unpredictable. Before advancements in shipbuilding and navigation, the uncertainty of sea voyages led people to rely heavily on deities. As immigrants settled in the western plains, the Mazu belief took root and became one of Taiwan’s most representative folk beliefs.

Mazu, Heavenly Mother

The Mazu belief has expanded beyond Taiwan’s coastal areas. Originally concentrated along the coastal plains, Mazu temples are now found across the island, from bustling urban streets to remote mountain. These temples embody the history of struggles with the sea and reflect Taiwan’s social changes and development. In the face of unpredictable disasters and challenges, traditional beliefs provided comfort and explanations from the island’s earliest days. One famous modern legend about Mazu is her miraculous intervention during World War II when Taiwan was bombed by the U.S.military. Reports from towns like Lukang, Beigang,Puzi, Yanshui, and Wandan tell of Mazu supposedly catching bombs with her hands or skirt, protecting residents and preventing destruction. This divine maternal love became a symbol of hope for those enduring hardship.

People used to rely on faith to pray for favorable weather and safety. Nowaday where typhoon paths 1,000 kilometers away can be accurately predicted by AI, many everyday fears once addressed by deities can now be predicted and mitigated by science. However, we are still powerless to cope with the rapidly changing society. Compared to the stable argricutural society, people feels more alienating and lonely today. The Xiahai Chenghuang Temple in Taipei is one of the well-known temples in the northern region, which was once a bustling place of worship. In recent years, it has gained popularity among young people who come to seek blessings from the God of Marriage, and even tourists from Japan and Korea.

Xiahai Chenghuang Temple

Majo Ussat。Photo by Majo Ussat

Xiahai Chenghuang Temple

Majo Ussat。Photo by Majo Ussat

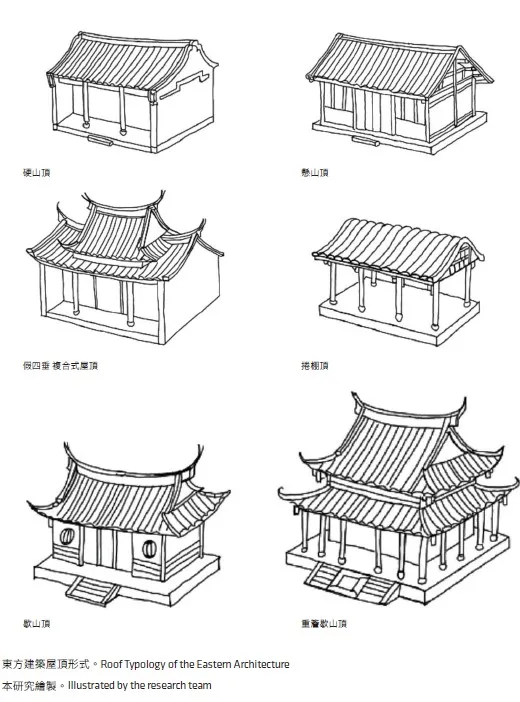

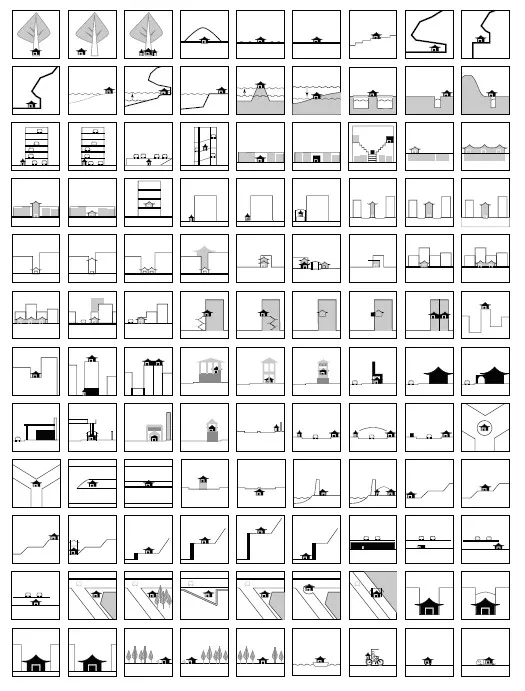

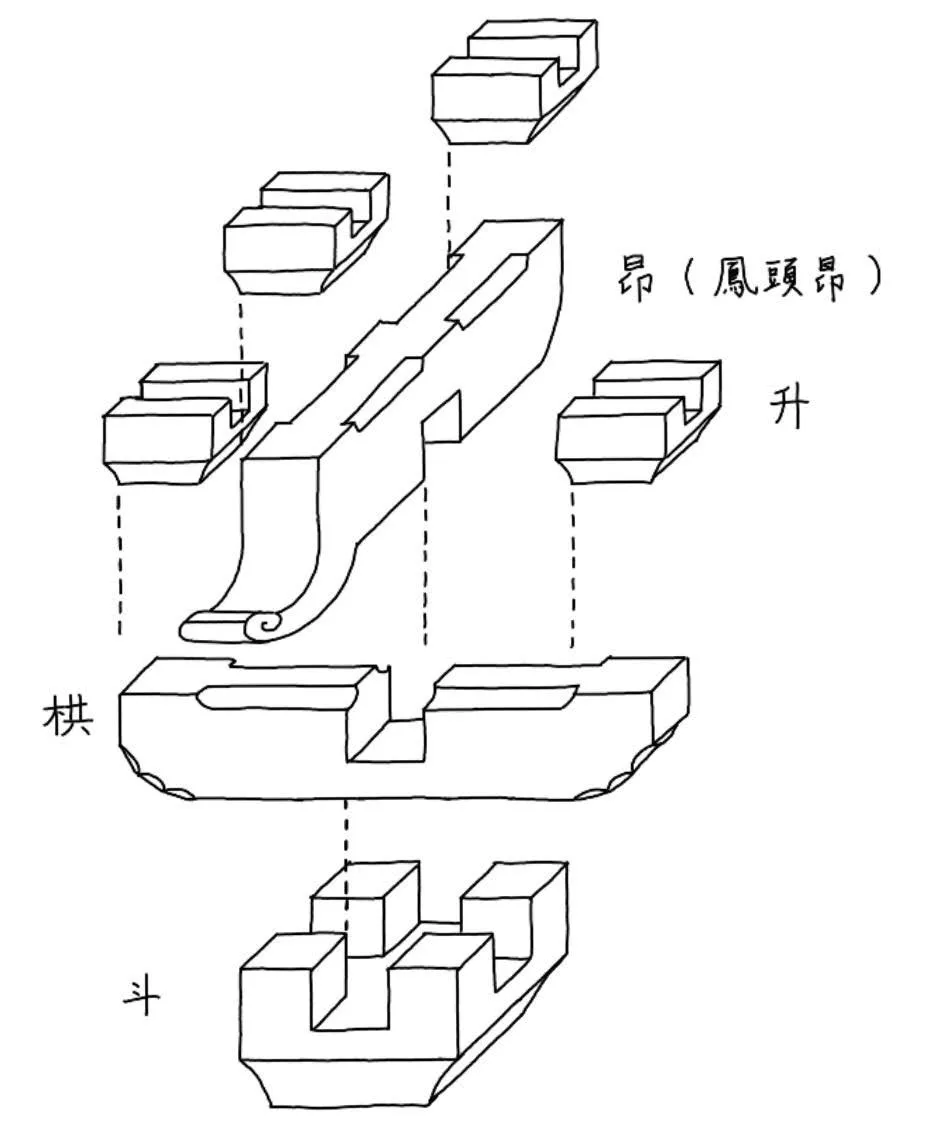

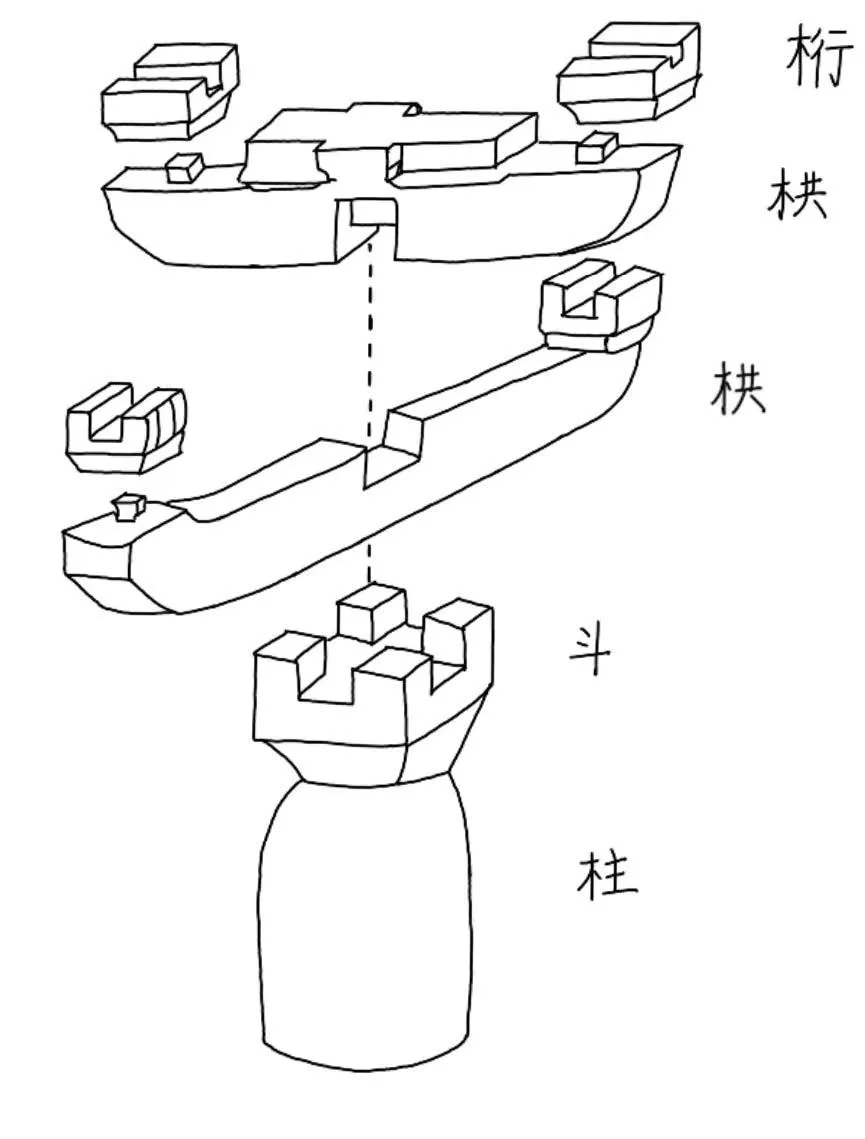

Typology of East Religious Architecture

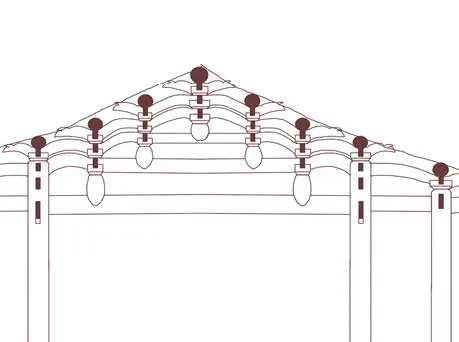

Roof Typology of the Eastern Architecture Illustrated by the research team

In terms of typology, Eastern religious buildings do not have a distinct architectural type like Western churches. Traditional Eastern architecture is primarily distinguished by the complexity of its structure, which reflects the building’s rank rather than its functionality. Traditional buildings in East Asia, located within the monsoon belt, are designed to withstand the heavy rainfall during summer. A key feature is the large, sloping roof that extends beyond the walls, quickly directing rainwater away.While Western architecture often expresses the building’s identity through its facade, in East Asia,the complexity of the roof reflects its social status.From China, Korea, and Japan to Vietnam, Malaysia,and Indonesia, various forms of large roofs can be seen in traditional architecture. Beneath these expansive roofs, the eaves extend beyond the walls,requiring cantilever beams for structural support. In times when labor was inexpensive, this cantilever gradually evolved from a physical necessity into a highly decorative element. The cantilever beam developed into a slanted support beam, which then evolved into a bracket and horizontal beam system, utilizing smaller materials to interlock and distribute the roof’s weight.

Since the Song Dynasty, when the Yingzao Fashi(Treatise on Architectural Methods) was written and established as a standard, the roof design, the number of bays in the facade, and the complexity of the dougong (bracket system) have all been important representations of status in East Asian architecture for over a thousand years. The traditional interiors in East Asian buildings are dim and profound, creating a mysterious and solemn atmosphere. This is closely related to the strong spring and summer rainfall in the East Asian monsoon belt and the available building materials.The overlapping dougong system renders roof openings meaningless, and actively creating openings in the roof, which could become potential points of water leakage, was unthinkable in the past. The use of transparent glass as a building material only became available in the East in modern times. As a result, the dim and mysterious religious spaces in the East stand in stark contrast to the high windows of Western churches, which use light to symbolize heaven.

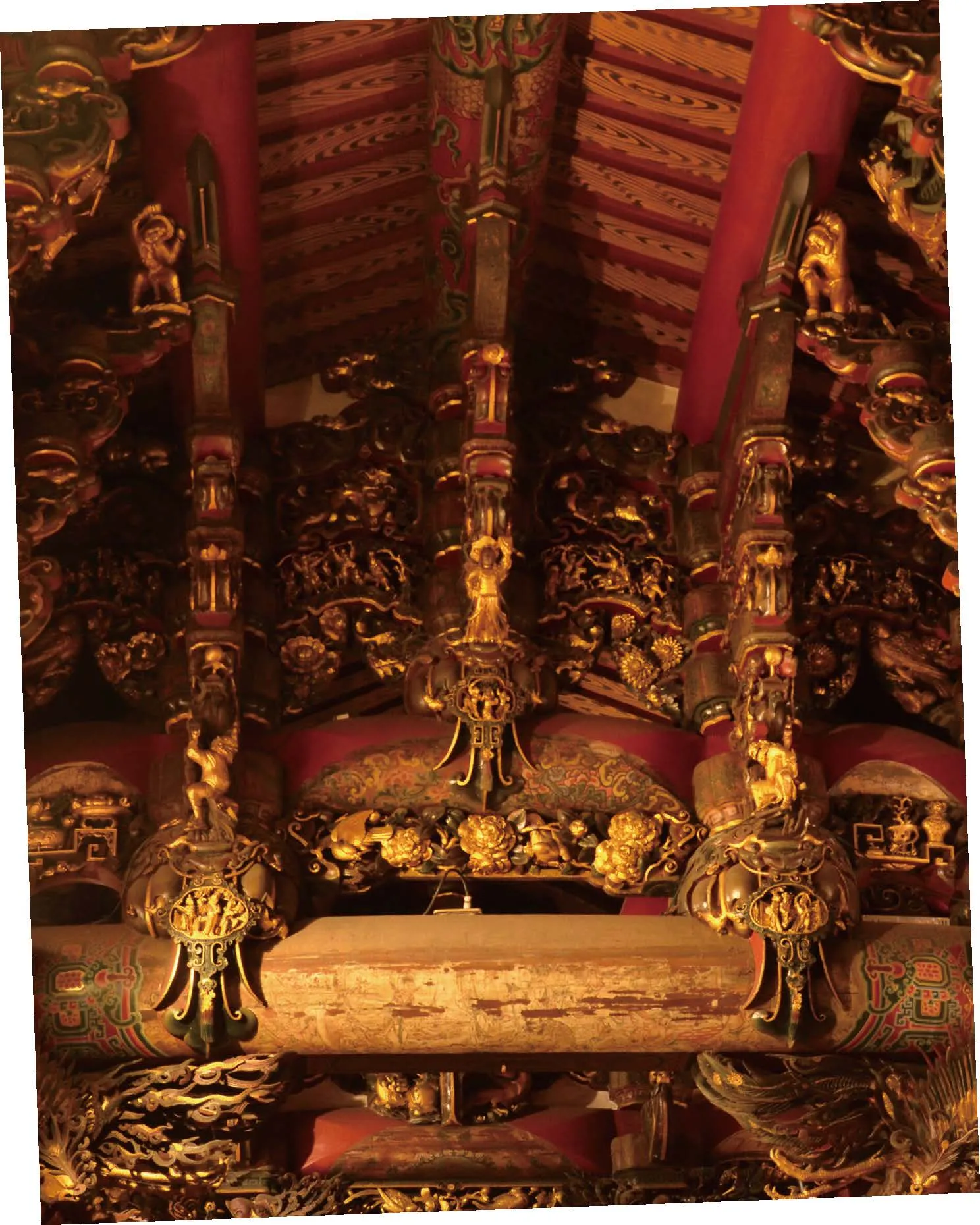

The Roof Structure of Beigang Chaotian Temple

Photo by Yu-Hua Tsai

The Roof Structure of Beigang Chaotian Temple

Photo by Yu-Hua Tsai

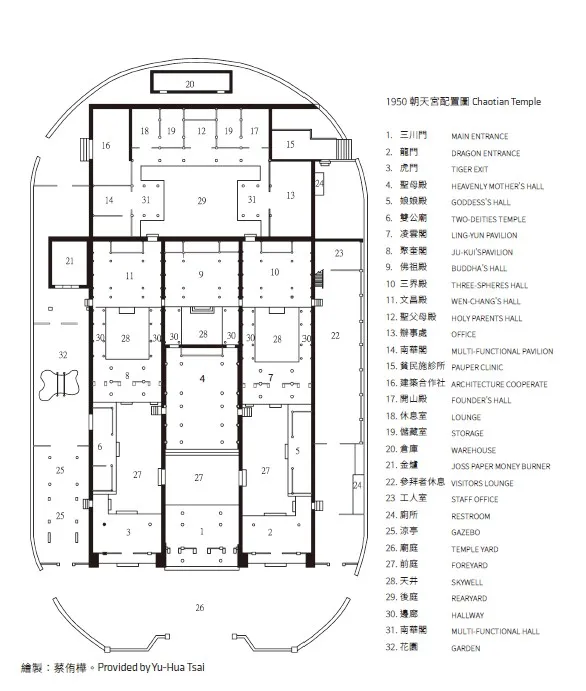

Beigang Chaotian Temple

Taiwan’s folk religious architecture, which was introduced by early settlers hundreds of years ago,is often associated with temples featuring upwardcurved eaves, intricate dougong structures, and vibrant red walls and yellow roof tiles. One of the most renowned temples in Taiwan’s Mazu belief is the Beigang Chaotian Temple(North Harbor Toward Sky Temple). Established at the end of the 17th century, the temple enshrined the statue of Mazu from the Chaotian Pavilion in Meizhou, Fujian,China and was set up in the then-Jhuluo Ben Port of Taiwan. With a history of over three hundred years, the temple has long been a protector of the seafaring people. After many years of expansion,the current Chaotian Temple occupies nearly 3,300 square meters. From the research of Professor Yu-Hua Tsai from the Department of Architecture at National Cheng Kung University, we can see the complete and impressive spatial arrangement of Beigang Chaotian Temple. The temple complex is divided into four sections, with the second section serving as the main hall, also known as the Heavenly Mother Hall, built on a platform raised 70 centimeters above the ground. The hall is divided into front and rear sections, with a roll-up roof in the front and a gabled roof in the back. The two sections are connected by a water trough. From the large wooden structure to the intricate carvings,cut-and-paste decorations, and colorful paintings,every detail showcases exceptional craftsmanship,and these artistic achievements reflect the sincere faith of the devotees.

Belief is the deepest form of spiritual solace, and people always respond to their belief with the best they have. In terms of religious architecture, it was common in the past to employ the most advanced technology available to construct spaces for worship. The main hall of Beigang Chaotian Temple was originally built with large timber construction and, since its establishment in the late 17th century,has been one of the most remarkable examples of Minnan-style timber architecture in Taiwan. In the 1960s, the main hall housing the Mazu statue was reconstructed into reinforced concrete.

In the 1950s, Taiwan gradually embraced American technology and materials through the support of U.S. aid. Reinforced concrete, as a representative of modern architecture, entered Taiwan in large quantities. Known for its superior structural performance and durability, reinforced concrete buildings quickly gained popularity in Taiwan, with even religious buildings adopting this emerging construction technology in a short period. However,even in a temple primarily made of reinforced concrete, what the devotees still recognized and appreciated was the familiar image: the sloping roof, curved eaves, intricate dougong structures,and vibrant red walls with yellow roof tiles. From the perspective of reinforced concrete’s structural properties, a simple cantilever beam would have been sufficient to address the cantilever issue. However, to meet the expectations of the faithful, Taiwanese craftsmen preserved these traditional temple elements, using reinforced concrete to replicate the architectural features of timber construction, much like how ancient Greek architecture used stone to imitate the characteristics of original wooden structures.

Taiwan’s folk religious architecture, which was introduced by early settlers hundreds of years ago,is often associated with temples featuring upwardcurved eaves, intricate dougong structures, and vibrant red walls and yellow roof tiles. One of the most renowned temples in Taiwan’s Mazu belief is the Beigang Chaotian Temple(North Harbor Toward Sky Temple). Established at the end of the 17th century, the temple enshrined the statue of Mazu from the Chaotian Pavilion in Meizhou, Fujian,China and was set up in the then-Jhuluo Ben Port of Taiwan. With a history of over three hundred years, the temple has long been a protector of the seafaring people. After many years of expansion,the current Chaotian Temple occupies nearly 3,300 square meters. From the research of Professor Yu-Hua Tsai from the Department of Architecture at National Cheng Kung University, we can see the complete and impressive spatial arrangement of Beigang Chaotian Temple. The temple complex is divided into four sections, with the second section serving as the main hall, also known as the Heavenly Mother Hall, built on a platform raised 70 centimeters above the ground. The hall is divided into front and rear sections, with a roll-up roof in the front and a gabled roof in the back. The two sections are connected by a water trough. From the large wooden structure to the intricate carvings,cut-and-paste decorations, and colorful paintings,every detail showcases exceptional craftsmanship,and these artistic achievements reflect the sincere faith of the devotees.

Belief is the deepest form of spiritual solace, and people always respond to their belief with the best they have. In terms of religious architecture, it was common in the past to employ the most advanced technology available to construct spaces for worship. The main hall of Beigang Chaotian Temple was originally built with large timber construction and, since its establishment in the late 17th century,has been one of the most remarkable examples of Minnan-style timber architecture in Taiwan. In the 1960s, the main hall housing the Mazu statue was reconstructed into reinforced concrete.

In the 1950s, Taiwan gradually embraced American technology and materials through the support of U.S. aid. Reinforced concrete, as a representative of modern architecture, entered Taiwan in large quantities. Known for its superior structural performance and durability, reinforced concrete buildings quickly gained popularity in Taiwan, with even religious buildings adopting this emerging construction technology in a short period. However,even in a temple primarily made of reinforced concrete, what the devotees still recognized and appreciated was the familiar image: the sloping roof, curved eaves, intricate dougong structures,and vibrant red walls with yellow roof tiles. From the perspective of reinforced concrete’s structural properties, a simple cantilever beam would have been sufficient to address the cantilever issue. However, to meet the expectations of the faithful, Taiwanese craftsmen preserved these traditional temple elements, using reinforced concrete to replicate the architectural features of timber construction, much like how ancient Greek architecture used stone to imitate the characteristics of original wooden structures.

Beigang Chaotian Temple’s yard

Beigang Chaotian Temple’s yard

Incense Burner at the Foreyard

Incense Burner at the Foreyard

Procession and incense pilgrimage

Procession and incense pilgrimage

Heavenly Mother’s Hall

Photo by Yu-Hua Tsai

Heavenly Mother’s Hall

Photo by Yu-Hua Tsai

Heavenly Mother’s Hall (the highest in the photo) has been reconstruted into RC in the 1960’s

Photo by Yu-Hua Tsai

Heavenly Mother’s Hall (the highest in the photo) has been reconstruted into RC in the 1960’s

Photo by Yu-Hua Tsai

The Main Street in Front of the Temple, one can see the religious freedon of the Taiwanese. (The yellow sinage said”one should repent and believe in Jesus)

Photo by Yu-Hua Tsai

The Main Street in Front of the Temple, one can see the religious freedon of the Taiwanese. (The yellow sinage said”one should repent and believe in Jesus)

Photo by Yu-Hua Tsai

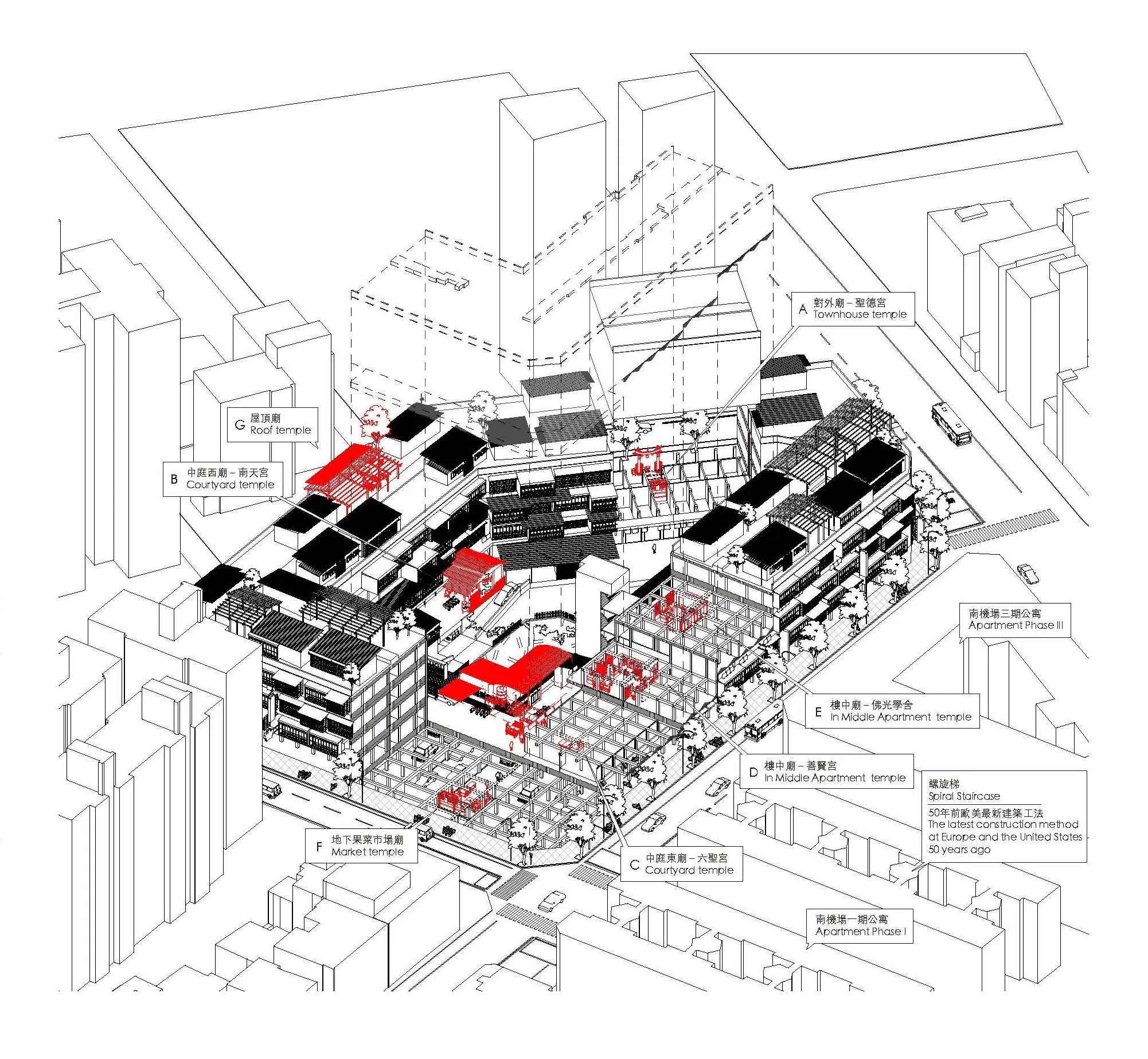

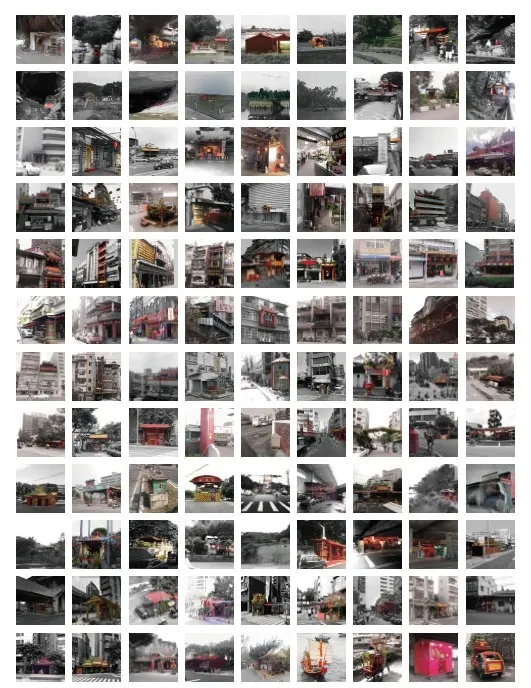

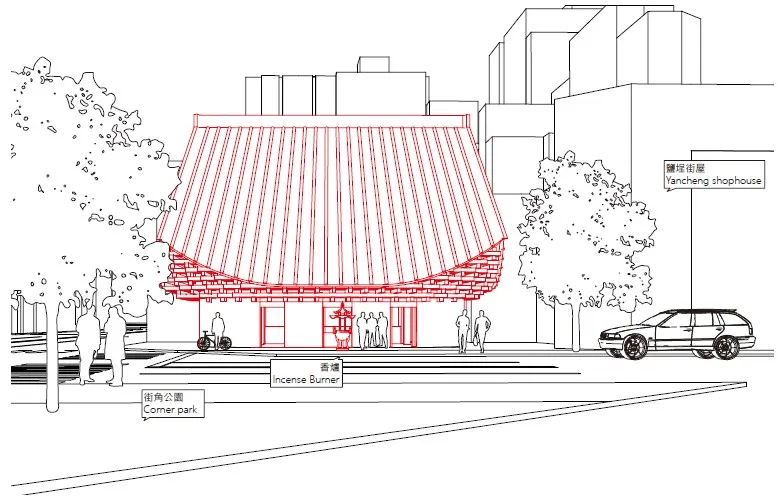

Parasitic Temples

As Taiwan transitioned from an agricultural society to an industrial and commercial society, a large population flocked to the cities. Today, Taiwan has one of the highest urbanization rates in the world, with nearly 80% of its population residing in urban areas. As the population concentrated in cities, religious spaces also moved from rural areas to urban environments. In the past, temples were often independently established within settlements, but with the increasing scarcity of urban land resources, these spaces of faith began to integrate with various urban spaces. In architect Bo-wei Lai ‘s work Parasitic Temples, we see how Taiwanese urban street temples adapt to societal changes in the narrow gaps of the city.Due to the uniqueness and sacredness of religious architecture, these temples exist in every corner of the city in the most imaginative ways. The emotional attachment to tradition has led building and management authorities to tacitly accept their presence.

Townhouse Temple: Leshan Temple in Taipei

Photo provided by Po-Wei Lai

Townhouse Temple: Leshan Temple in Taipei

Photo provided by Po-Wei Lai

Underbridge Temple

Photo provided by Po-Wei Lai

Underbridge Temple

Photo provided by Po-Wei Lai

Traffic Island Temple

Photo provided by Po-Wei Lai

Traffic Island Temple

Photo provided by Po-Wei Lai

Slice Temple

Photo provided by Po-Wei Lai

Slice Temple

Photo provided by Po-Wei Lai

In Taiwan’s urbanization process, the quantity of space takes priority. Take the Second Apartment Building of Nanjichang in Taipei as an example.To maximize the number of households, the residential spaces are extremely small. The circular corridor between the units is fully occupied by residents, who claim the missing space for purposes such as laundry or religious activities. The entire Nanjichang complex houses seven temples,including three converted temples on the ground floor, two in-between-floor temples, a market temple, and one rooftop temple. Although these temples are managed by different individuals, no factions have emerged, which best reflects the common people’s universal belief in gods.

The Nanjichang complex has now stood for over 50 years, and its architecture no longer meets contemporary needs. At the same time, as traditional folk religious spaces gradually detach from everyday necessities and the older generation diminishes, will these religious spaces, tucked away in the corners of the city, continue to exist in the future?

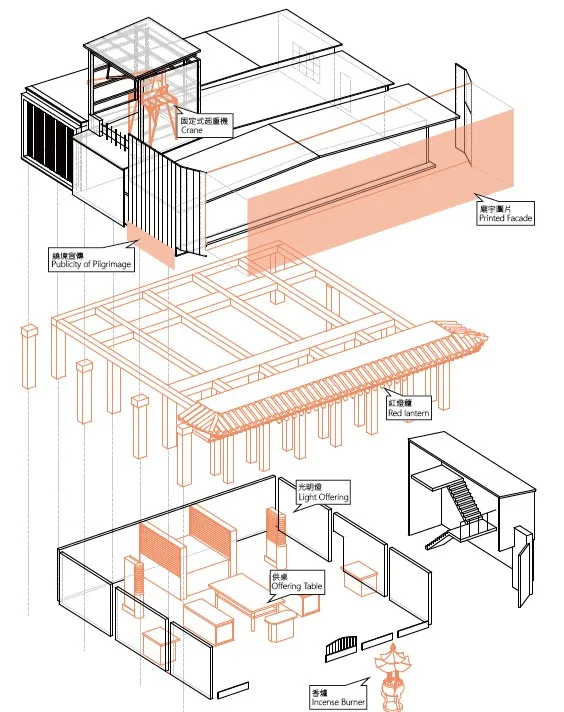

Chaohou Temples of the Salt Pan

In early 2024, a Mazu temple located by the Kaohsiung port reached out to us with a request.The temple sought to design a new Mazu temple within a limited budget, one that would be easily understood by the believers. The goal was to attract young devotees back to the temple. Kaohsiung Chaohou Temple, a branch of Beigang Chaotian Temple, was established by the Yunlin County Association after relocating to Kaohsiung. It is situated by the Love River in Yancheng District, an area that was once a salt pan. Every year, during the third month of the lunar calendar, the faithful walk to Beigang to participate in the pilgrimage.

Mazu Statue of Chaohou Temple

Mazu Statue of Chaohou Temple

The current building is a steel structure,demonstrating the flexibility of Taiwanese architecture. The first floor serves as the primary religious space. Traditionally, temple spaces were limited to the ground level due to structural constraints, but Chaohou Temple includes a second floor, used for storing items needed for the pilgrimage, such as palanquins, gongs, drums,and other ceremonial objects. The building has a large opening on the side, through which a crane lifts the palanquins to the second floor for storage.The front façade is decorated with sloping eaves and incorporates intricate bracket structures, along with vibrant yellow roof tiles and red columns.These symbols are intended to evoke an emotional connection with the traditional temples. The”facade” features a photo of Beigang Chaotian Temple, with the name digitally altered to Chaohou Temple. This image is printed on canvas and wrapped around the lightweight steel structure.

The Facade of Chaohou Temples

The Facade of Chaohou Temples

The statue of Mazu and her generals in front of the palanquin, Thousand-Mile Eye and Wind-Following Ear.

The statue of Mazu and her generals in front of the palanquin, Thousand-Mile Eye and Wind-Following Ear.

The top image was taken in 2025, and the bottom image in 2024. The three typhoons that struck Taiwan in 2024 caused the large trees by the riverbank to lose half of their foliage.

The top image was taken in 2025, and the bottom image in 2024. The three typhoons that struck Taiwan in 2024 caused the large trees by the riverbank to lose half of their foliage.

The Axonometric Diagram of Chaohou Temple

The Axonometric Diagram of Chaohou Temple

Chaohou Temple by Love River, side opening with a crane. The chimney of the furnace extanded to the roof

Chaohou Temple by Love River, side opening with a crane. The chimney of the furnace extanded to the roof

The faithful walk to Beigang to participate in the pilgrimage.

The faithful walk to Beigang to participate in the pilgrimage.

Provided by Chaohou Temple

Provided by Chaohou Temple

The faithful walk to Beigang to participate in the pilgrimage.

Provided by Chaohou Temple

The faithful walk to Beigang to participate in the pilgrimage.

Provided by Chaohou Temple

Modern Traditional Timber Framing

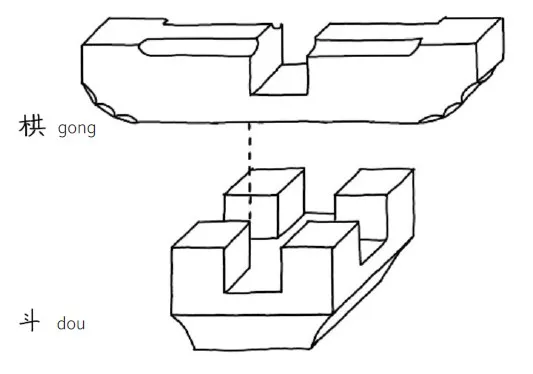

Once, when labor was inexpensive but building materials were scarce, architecture in the East Asian monsoon region developed the dougong (bracket) system. Today, with labor costs soaring,the budget for temple reconstruction cannot support the labor-intensive and intricate process of creating reinforced concrete dougong-style structures. The core challenge we face is how to construct a sacred space using current construction methods that address contemporary social issues,while resonating with both elderly and younger devotees alike.

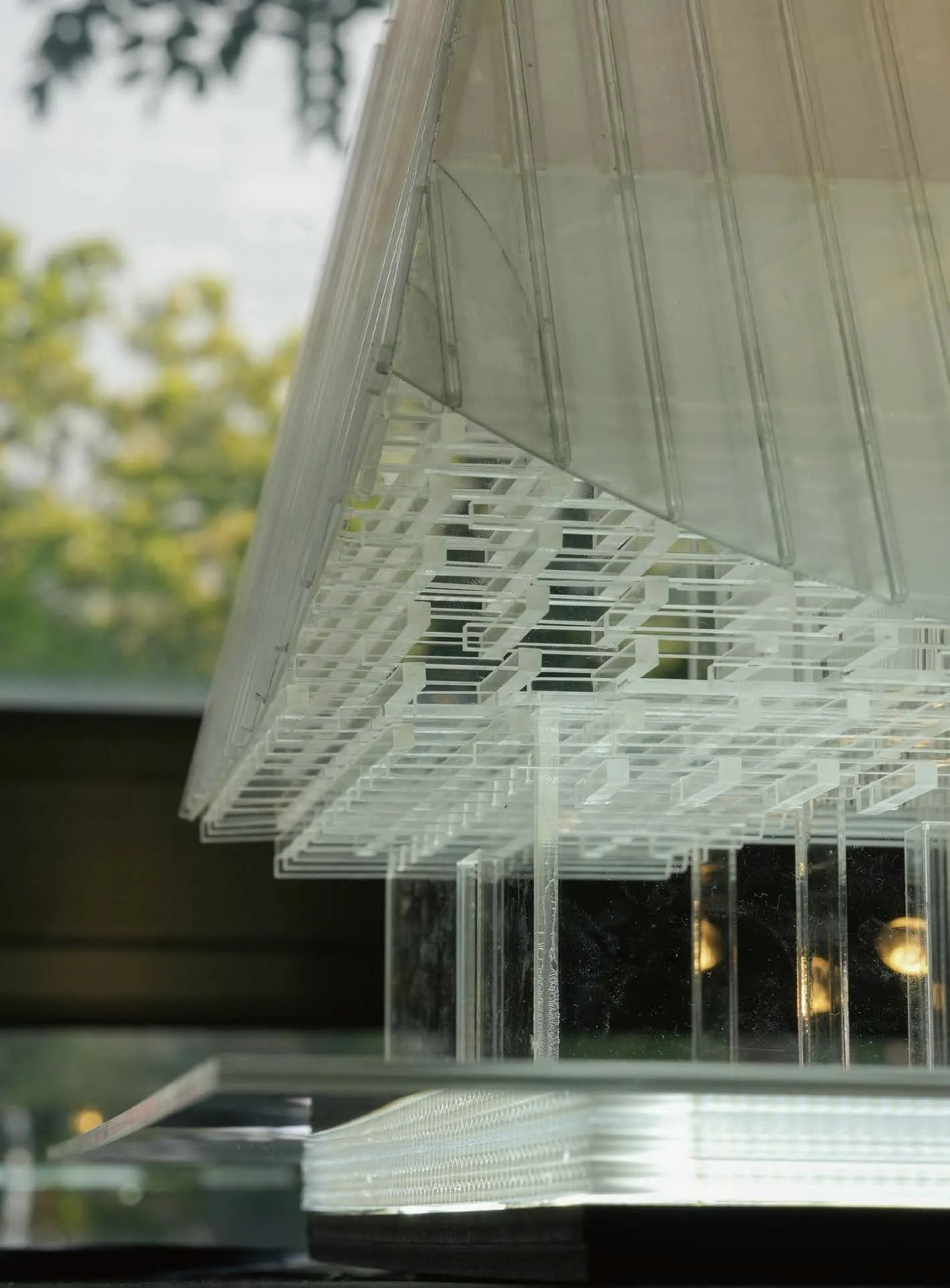

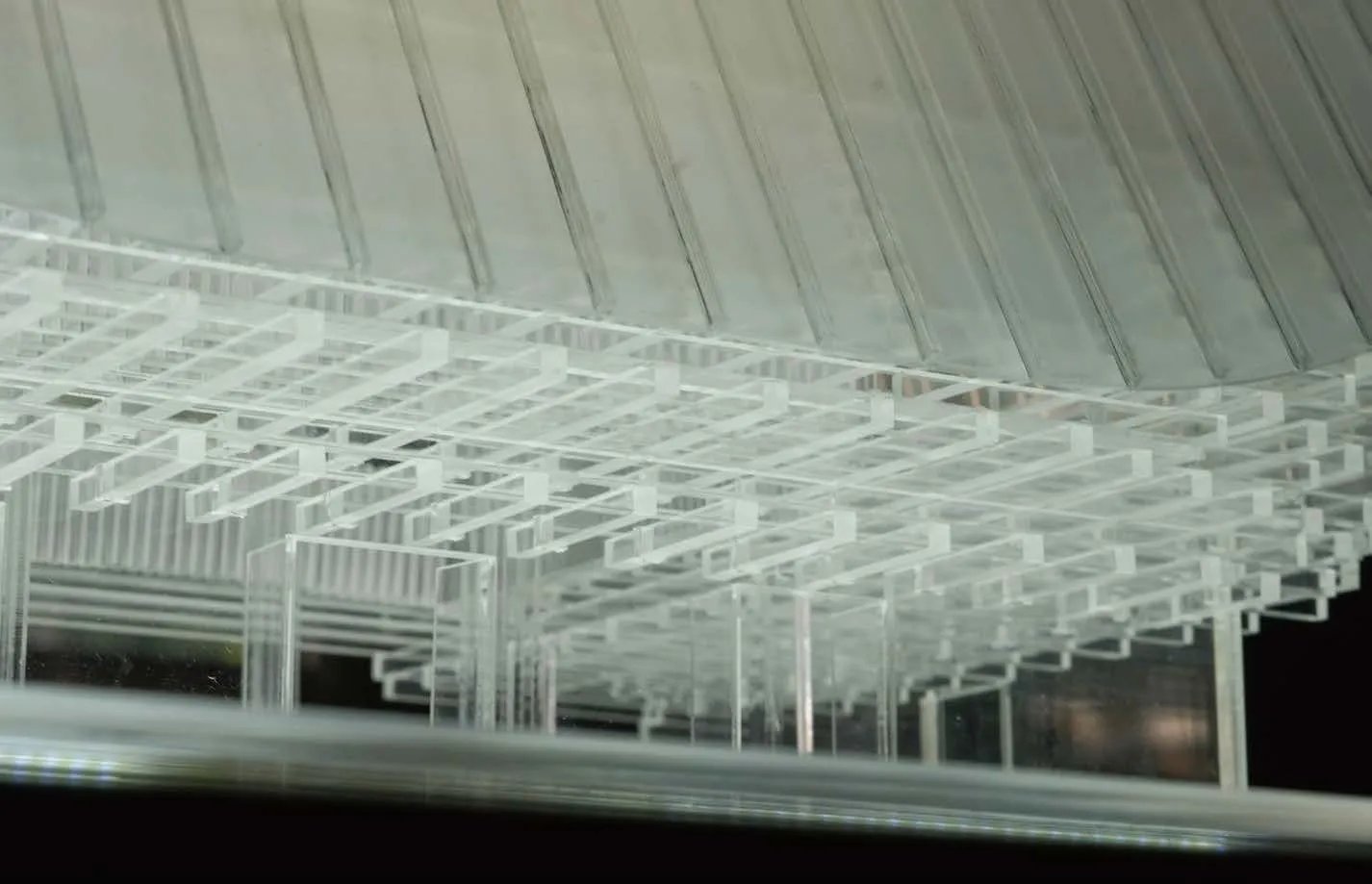

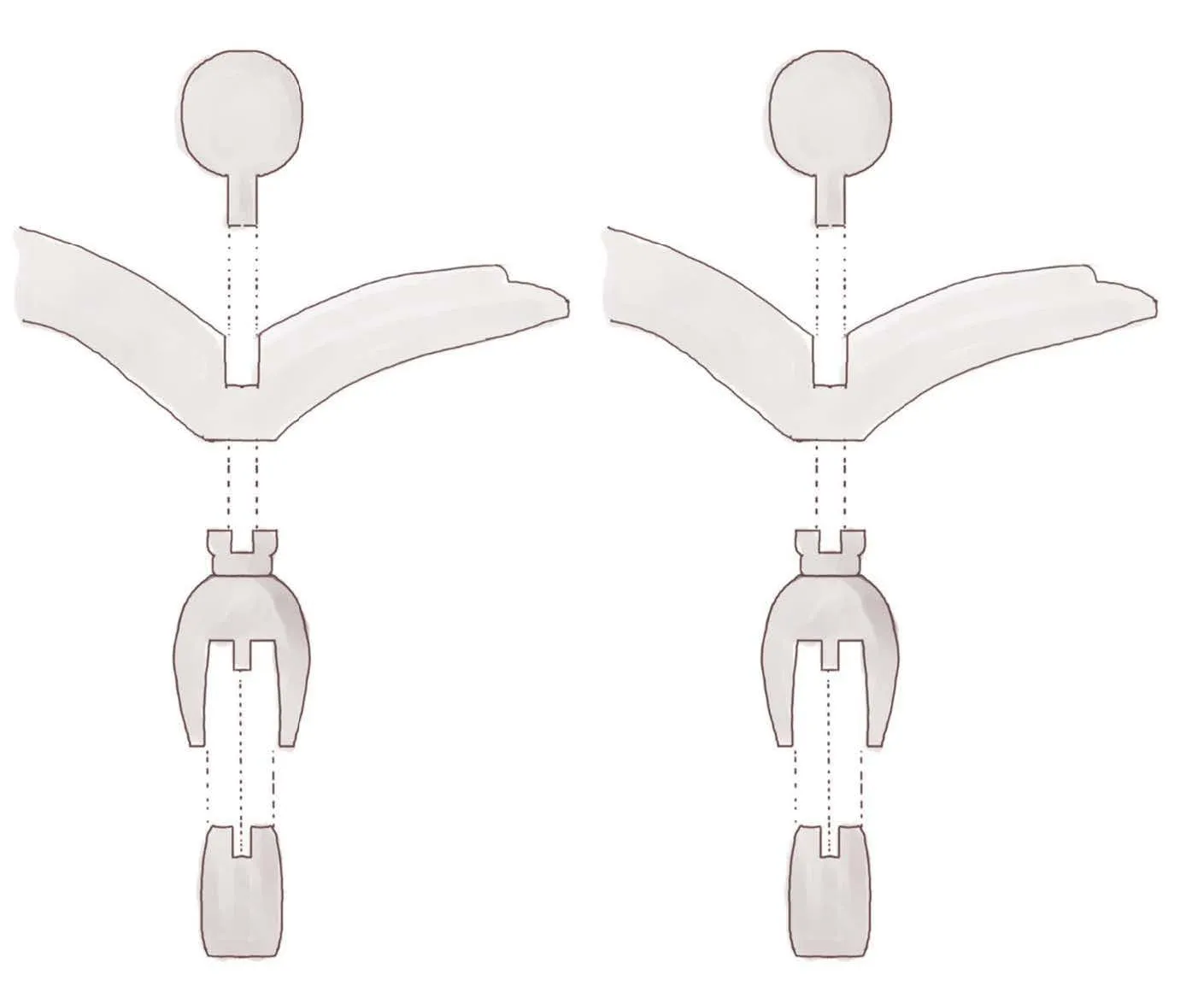

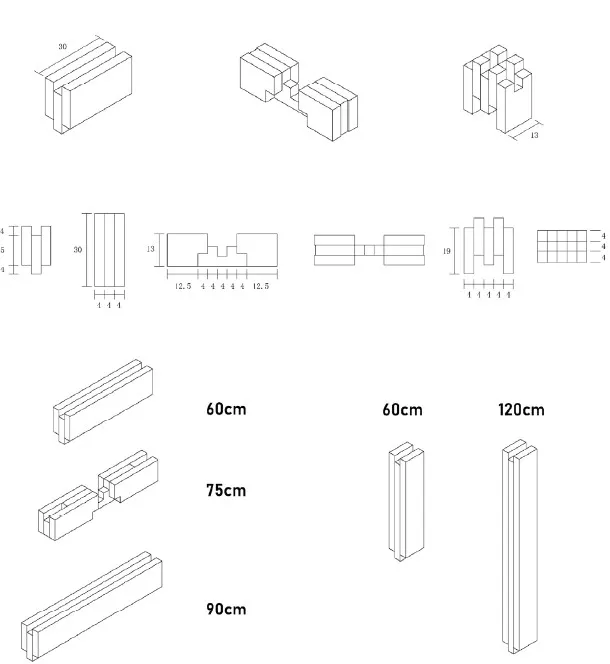

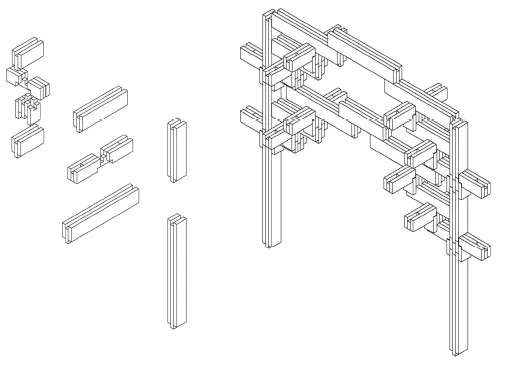

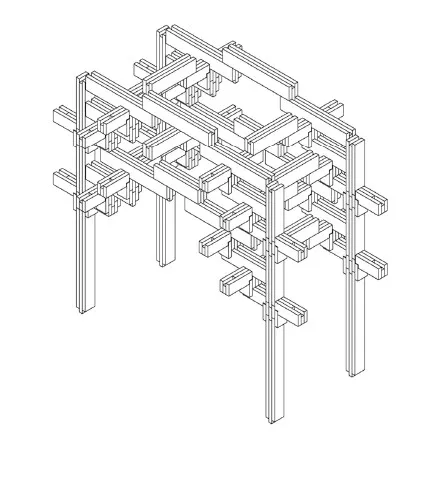

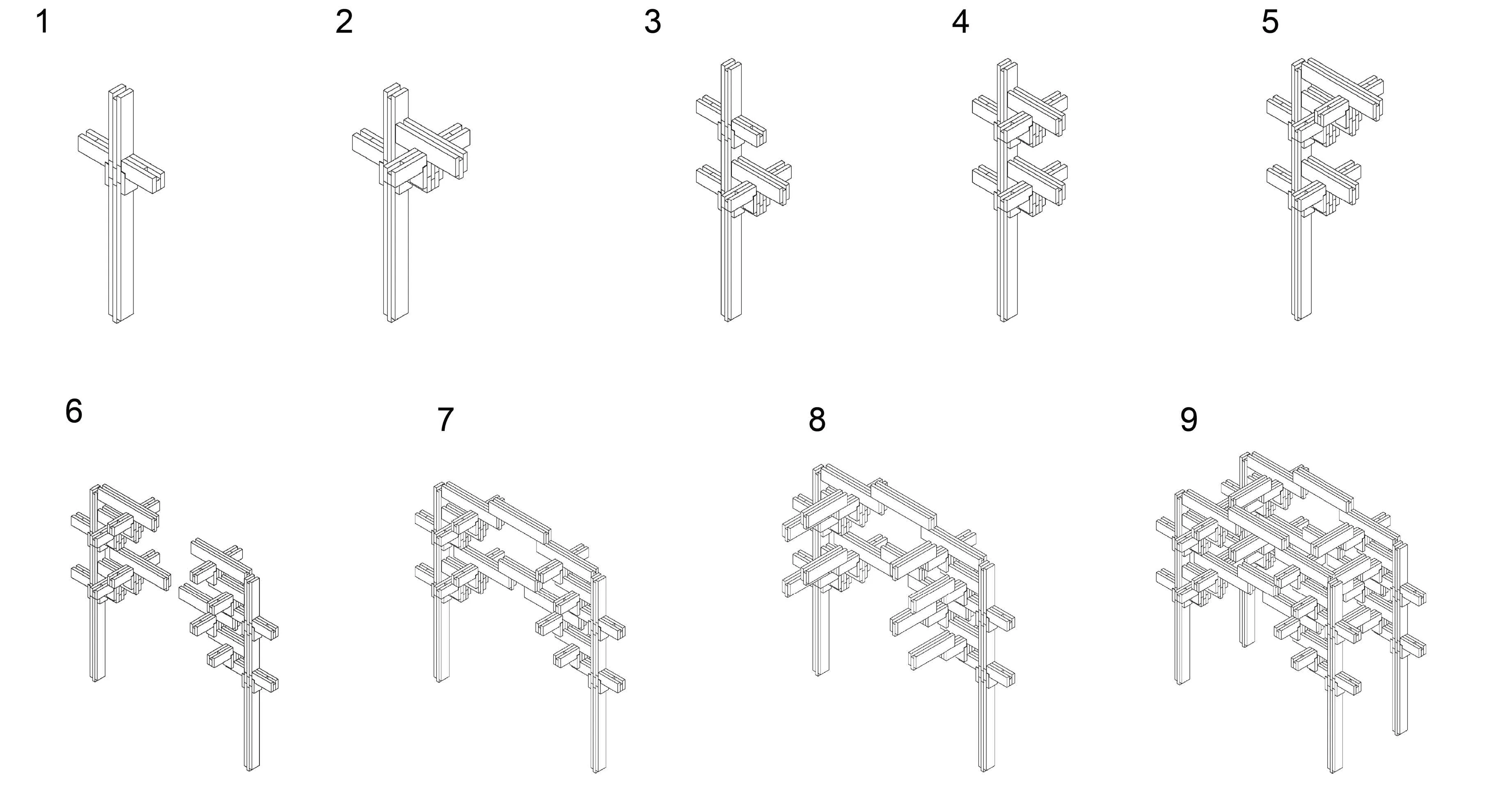

We propose using modern timber construction techniques to restore the structural function of the dougong system, which has often been reduced to a decorative element, and reinterpret traditional religious architecture. Over time,from cantilever beams to short brackets and arches, the mortise and tenon joints that connect them have become increasingly complex. The success of this structural system lies in the expertise of skilled large timber craftsmen.The dou, as a component that supports the small horizontal beams (i.e., the arches) above, must have grooves carved into a single piece of timber during its production process to ensure the upper beams fit securely. Before the advent of the chemical industry and strong adhesives capable of withstanding lateral forces, the dou relied solely on the physical properties of the wood fibers to bear such forces.

We propose using modern timber construction techniques to restore the structural function of the dougong system, which has often been reduced to a decorative element, and reinterpret traditional religious architecture. Over time,from cantilever beams to short brackets and arches, the mortise and tenon joints that connect them have become increasingly complex. The success of this structural system lies in the expertise of skilled large timber craftsmen.The dou, as a component that supports the small horizontal beams (i.e., the arches) above, must have grooves carved into a single piece of timber during its production process to ensure the upper beams fit securely. Before the advent of the chemical industry and strong adhesives capable of withstanding lateral forces, the dou relied solely on the physical properties of the wood fibers to bear such forces.

Given the current shortage of both labor and materials, we must find a contemporary path for large timber construction.

Dou Gong, Asian Bracket System

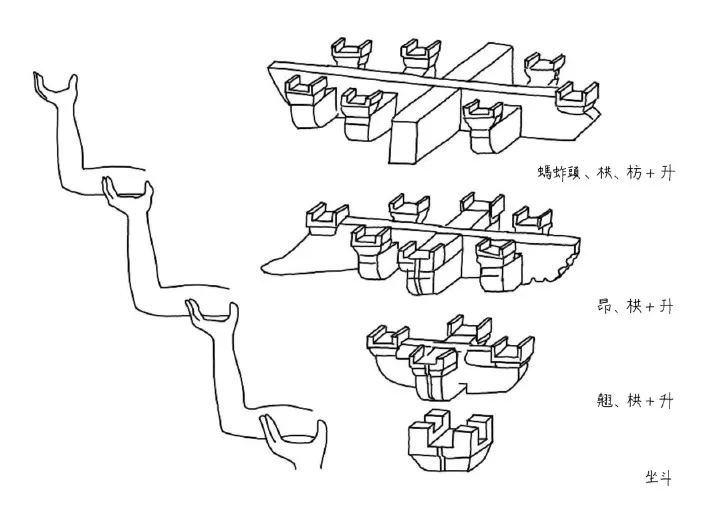

The large roofs under the East Asian monsoon belt require a structural form that effectively distributes the weight of the roof. The so-called “dougong”(a traditional bracket system) consists primarily of a bracket that bears vertical forces and an arch with horizontal beams, channeling the distributed weight to the columns. Over time, the structure became more and more complex. These building components also played a role in the Confucian society in classifying the hierarchy of buildings,with regulations regarding the size and number of the dougong.

The large roofs under the East Asian monsoon belt require a structural form that effectively distributes the weight of the roof. The so-called “dougong”(a traditional bracket system) consists primarily of a bracket that bears vertical forces and an arch with horizontal beams, channeling the distributed weight to the columns. Over time, the structure became more and more complex. These building components also played a role in the Confucian society in classifying the hierarchy of buildings,with regulations regarding the size and number of the dougong.

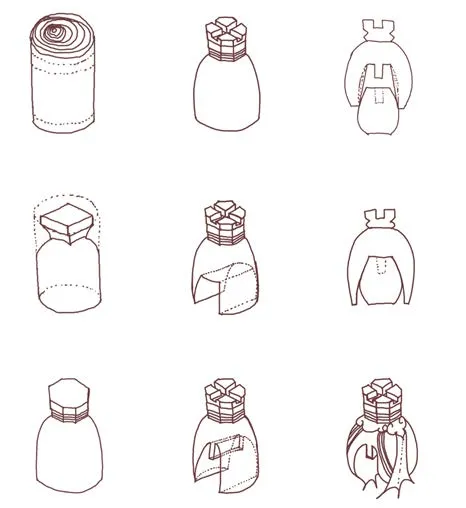

Preservation with Latest Technique

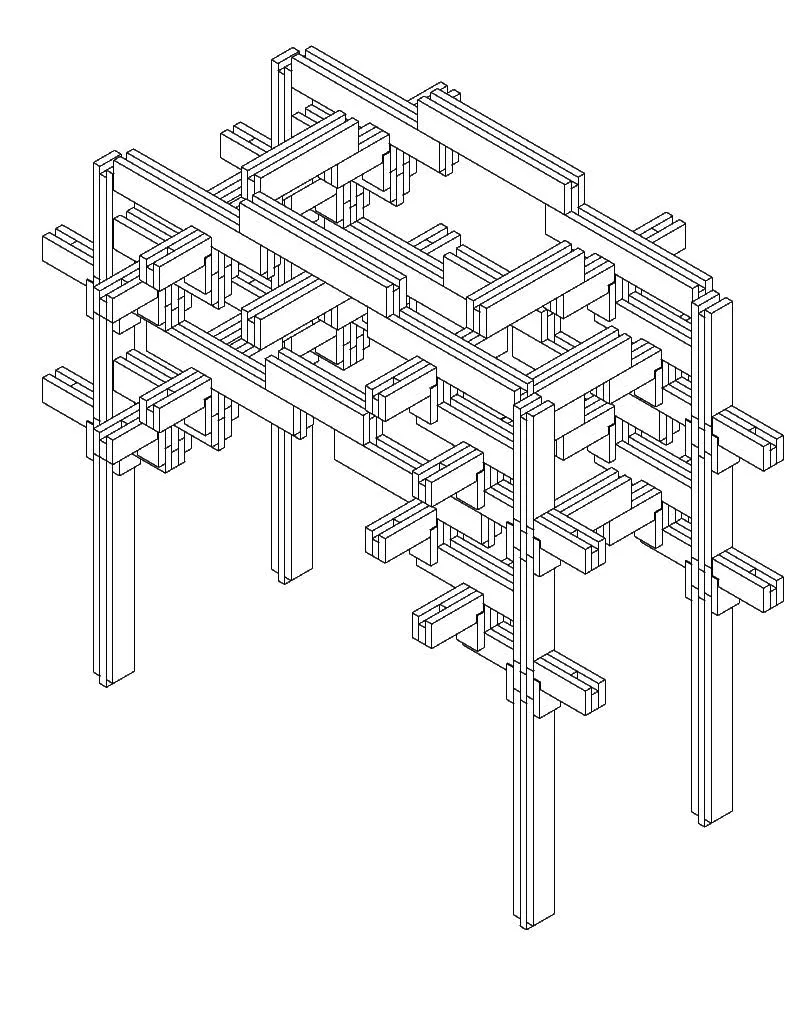

Today, fewer people choose labor-intensive industries as their life’s work, and with the severe labor shortage in the construction industry, we have collaborated with Professor Yu-xiang Ye from the Department of Architecture at National Cheng Kung University. By drawing on traditional joinery techniques, we aim to reduce labor input through construction automation, while creating products that evoke people’s memories of traditional large timber construction. This research focuses on the guatong (melon-shaped) component in the stacked dou construction method. In the past, this required a single piece of timber to be manually hollowed out, but now it is modified by cutting the guatong into several pieces, each CNC-machined to the required concave and convex dimensions. Finally, bolts are used to secure the parts together, creating a mortise-and-tenon structure. Multiple units are then repeatedly connected to form a frame system that can bear the weight of the roof.

New Timber Framing System

New Timber Framing System

Melon Columns

Before the advent of chemical adhesives,commonly available adhesives were mostly made from natural materials, such as glutinous rice or shell lime, which could not effectively resist lateral forces. Another potential method for material connection involved using metal fasteners, but anti-corrosion techniques were poor, and the costs were too high then. The most reasonable method for material connection relied on materials itself.This is also why traditional structures had to be completed through mortise and tenon joints.

For example, the construction of a stacked dougong(bracket) framework involved layers of beams that transferred the roof’s forces down to the columns.The short columns between the beams, shaped like melons, connected the upper and lower parts.In the image on the right, you can see different types of melon-shaped columns, all formed as a single piece. These structures relied on the inherent physical properties of the wood to achieve structural function. One can imagine how much effort craftsmen must have put into completing these intricate works.

Less Work, Better Timber

Currently, the number of traditional woodworkers in Taiwan has gradually diminished, and with today’s construction costs, it is often difficult to afford labor-intensive traditional methods. We are exploring a new approach that allows for the use of a largely automated construction model in future temple buildings while preserving a familiar atmosphere. We also hope to apply this method to the restoration of existing large wooden temples.

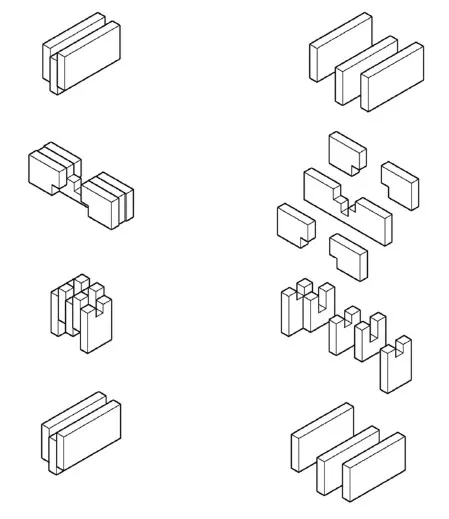

Drawing from the essence of traditional joinery techniques, we have sliced the dougong (bracket system) and used easily accessible standardized timber panels, which are CNC-machined and cut into the required convex and concave dimensions. The components are then secured together with bolts.This assembled dougong system can be repeatedly connected, using contemporary technology to help preserve and pass down traditional craftsmanship.

Modern timber construction technology allows the joint connections to have a higher resistance to damage than the material properties of the wood itself. Therefore, by disassembling and reassembling the vertical connecting components involved in the melon-shaped columns using a panel integration method, the resulting components retain the characteristics of traditional architecture but are easier to manufacture.

The materials are based on easily accessible timber specifications, with each panel cut to the required notches. Once assembled, they form dougong components—specifically the “ang,” “gong,” and”dou”—without the need for extensive carving.Considering larger-scale frame assembly, we combine the “sheng” construction method with the “gong,” resulting in 75 cm components. These components can be interconnected to change direction and vertically overlap.

The materials are based on easily accessible timber specifications, with each panel cut to the required notches. Once assembled, they form dougong components—specifically the “ang,” “gong,” and”dou”—without the need for extensive carving.Considering larger-scale frame assembly, we combine the “sheng” construction method with the “gong,” resulting in 75 cm components. These components can be interconnected to change direction and vertically overlap.

Extending from the initial three components,vertical and horizontal parts between 60 and 120 cm can be assembled into a framework simply using interlocking joints. The interfaces left at both ends of the 75 cm components allow for the infinite extension of the framework. This structure is not only easy to disassemble and reassemble but also allows for length adjustments using the same construction method.

Extending from the initial three components,vertical and horizontal parts between 60 and 120 cm can be assembled into a framework simply using interlocking joints. The interfaces left at both ends of the 75 cm components allow for the infinite extension of the framework. This structure is not only easy to disassemble and reassemble but also allows for length adjustments using the same construction method.

A Love Letter to Our Island

Whether a brand-new concept can be quickly accepted and integrated into mainstream values depends on whether the new idea or approach can effectively solve existing problems. Taking the example of temples designed with new wooden construction techniques, although the temple and its followers may not immediately embrace this proposal upon first encounter, we remain cautiously optimistic.

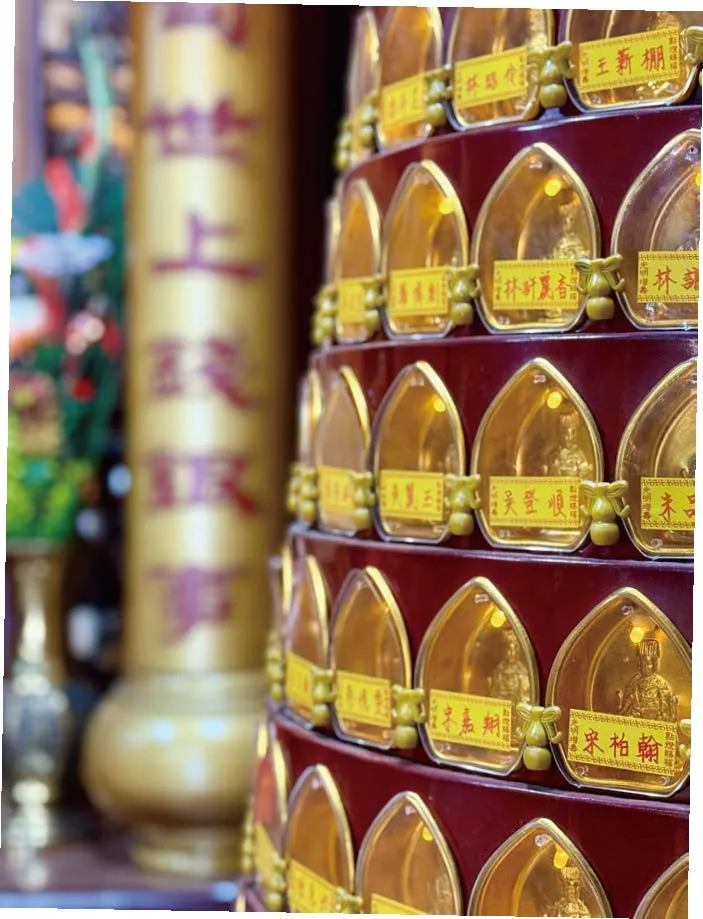

A common feature in Taiwanese temples is the tower-shaped votive lamps, which closely resemble the practice of lighting candles in Western churches. In the past, temples often placed thousands of candles or oil lamps on platforms in the temple courtyard, allowing believers to light the lamps as a symbol of “illuminating the future.”The revenue from votive lamps was also one of the important sources of income for many temples. By the 1960s, small light bulbs became more available,and some temples replaced traditional candles with small bulbs, transforming the original flat light candles into a tiered light tower. Each tier had small compartments for bulbs, and the exterior featured transparent windows with the names and birthdates of the devotees. This design of the light tower gradually spread widely in Taiwanese temples. Today, people often believe that temples should naturally have light towers, but in fact,this “new tradition” was invented and gradually popularized only in the past 50 years.

Once, facing health threats such as disease-carrying mosquitoes and infectious diseases, as well as unpredictable natural disasters like typhoons,earthquakes, and landslides, the folk beliefs not only provided explanations for the workings of the universe but also became a spiritual refuge for the ancestors. As scientific knowledge developed,these traditional explanations were gradually replaced by scientific perspectives. How should we view Taiwan’s folk belief architecture today?

Once, facing health threats such as disease-carrying mosquitoes and infectious diseases, as well as unpredictable natural disasters like typhoons,earthquakes, and landslides, the folk beliefs not only provided explanations for the workings of the universe but also became a spiritual refuge for the ancestors. As scientific knowledge developed,these traditional explanations were gradually replaced by scientific perspectives. How should we view Taiwan’s folk belief architecture today?

The Land God belief is another important folk belief in Taiwan, similar to the concept of “genius loci” in Roman culture. In the design of the Taichung Dahu Li Fude Temple, architect Yu-Ze Tai used the “Big roof” as a symbol of the temple’s extension into the earth, blending traditional and contemporary architectural vocabularies. Meanwhile, the temple initiated a donation campaign for votive lamps,using the diamond-shaped form of the lamps as a metaphor. In collaboration with the Department of Architecture at National Cheng Kung University (RAC-Coon), they used digital fabricated mold to connect digital design with manufacturing,reshaping Taiwan’s local religious spaces.

Big Roof made by the digital fabricated mold

Provided by TAI Architect & Associates

Big Roof made by the digital fabricated mold

Provided by TAI Architect & Associates

In the Taiwan Strait, the ocean currents are incredibly complex: to the west is the China coastal current flowing from north to south, while to the east, there is the Kuroshio Current branch flowing from south to north. As the force of the Kuroshio Current branch weakens as it moves north, it deposits the Yunlin-Changhua Rise off the coast,creating a shallow sandbank 30 to 40 meters deep.This area is one of the most promising wind power development zones in the world today. With the development of modern technology, this complex waterway has been transformed into a site for green energy. By February 2025, Taiwan’s wind power generation has exceeded 1300MW, providing green energy for the chip industry. The monsoons and ocean currents, once challenges for crossing to Taiwan, have now become Taiwan’s support.

The future is not the opposite of history. We cannot divide the past from the future based solely on today; the future is an accumulation of every yesterday and today. This Mazu temple is a love letter we write to this land. It responds to the hopes of the believers and contains our vision for the future of the city. The city we live in today is not perfect, but it is worth our efforts. We believe that by caring for the city, the architecture,and responding to the challenges of the social environment, our buildings will take root in this land.

Mazu Techple

Taiwan, situated between the largest landmass and the largest ocean, has its beliefs and NON-Beliefs shaped by the Kuroshio Current and monsoons.